Episode

Highlights

SHARING MATE

“The idea of mate, which I find really nice, is that is something meant to be shared. So you’re sharing with other people as you’re drinking. So you’re passing it and then people give it back to you to the person who is pouring down the water and then you give it to one of the person and so it’s a it’s a group thing them it is meant to be shared, which obviously I don’t do very often here because I don’t have anybody to share it with [laughter].”

—HERNÁN

Mate gourd, straw, and thermos | Photo: Credit

ARGENTINA IN CRISIS

“So one day he just woke up and he experienced really strange sound in his, I think his left ear. He went to the doctor. By the time he went there, he couldn’t hear any more from that ear. So it was due to stress that had killed these cells, and those cells don’t regenerate.”

—HERNÁN

Hernán is 15 at the time, living in the suburb of Buenos Aires where he had lived his whole life. And Argentina is going through a political and economic crisis.

To deal with this, Hernán turns to music.

“I started a band soon after that, and I was going to punk rock music concerts all the time. And that was very fun and being able to build community with other people.”

—HERNÁN

GOING TO JAPAN

“It was hard because I was alone without my family and friends for the first time, and I was only 18 years old. At that time, I thought that I could take it. And I thought that I could rule the world, you know? Cus I was 18. But also, yes, I was feeling a lot of loneliness and sadness. Even departing from a friend would feel like an anxious process because I was going back to a house that was empty because I was living by myself.”

—HERNÁN

Teenage Hernan in Tokyo | Photo:

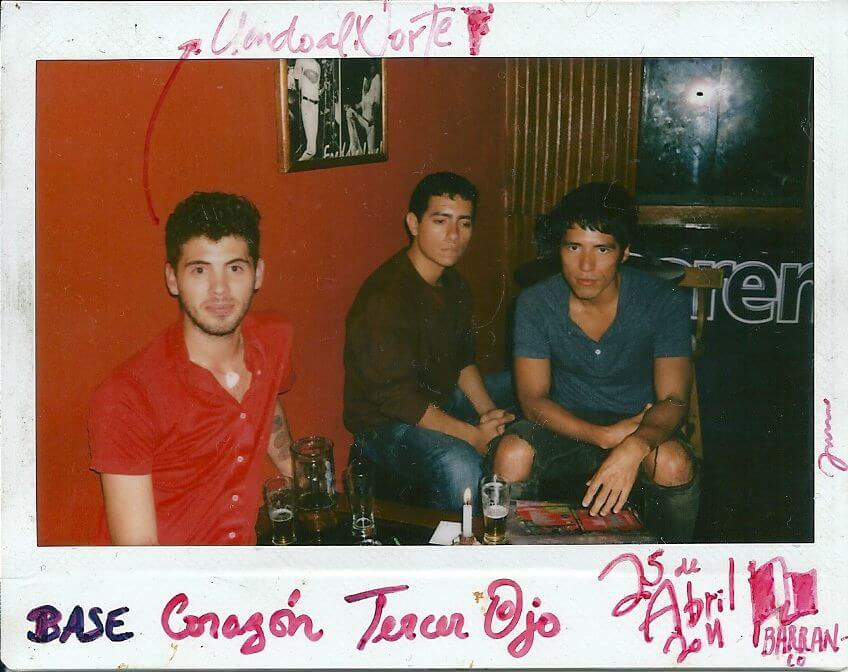

Hernan and friends in Peru | Photo:

COMING OUT

“I decided to confront my father and tell him these things about myself. And his reaction which was shocking to me at the time. Namely, he basically ostracized me. He said that he didn’t want to see me again. And so I said, Well, okay, what do I do?”

—HERNÁN

Busking on the street | Courtesy Hernán

Hernan in Argentina | Courtesy Hernán

A BACKPACK, GUITAR, AND A BUS TICKET

Hernán is showing me a crinkly map of South America with notes of dates and places and highlighted lines all over it. It’s the record of his trip from one end of the continent to the other.

“And this is pretty much the day before I was leaving. The only thing that I had with me was a backpack, a guitar and bus ticket out to Mendoza…”

—HERNÁN

“I think a thing that’s important to say is that I didn’t know when I was coming back, I had no agenda whatsoever. My only idea was to visit different places in Latin America and make sense of this traumatic experience I just had.”

—HERNÁN

END OF THE TRIP

“I was in Colombia when I didn’t know how to continue the trip.”

—HERNÁN

“I wanted to come to New York basically to see Bob Dylan live, and that’s what I did. I came up to New York with 200 bucks in my pocket, thinking that was a lot of money at the time. And in two weeks, I was broke, but I had seen Bob Dylan play live, and I was on my way to Chicago with a friend I had met through couchsurfing.”

—HERNÁN

LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT

“I saw him at the bar across a table. Just the way that I saw him —the baseball cap turned backwards, and his hair coming out kind of curly and his beard and his eyes, and there was just something that shone straight at me—I think made me really fall for him.”

—HERNÁN

Hernán, David and Jonathan travel together for the next week across the American West. They camp under the stars in Utah and see the deserts of Nevada. They travel all the way to San Francisco. And by the end of the trip, Hernán and Jonathan are in love.

DOMA

DOMA, or the Defense of Marriage Act, is a US federal law from 1996 that allows states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages and all the legal protections couples can get through marriage.

Which includes the green card sponsorship that a person with US citizenship can give their non-citizen fiancé. It’s 2013, though. And the Supreme Court is actually in the process of reviewing DOMA.

“We waited it out, basically. And DOMA became unconstitutional. And we were able to file papers so that I could come to the United States as a fiance. And that same year, we got married in Massachusetts.”

—HERNÁN

Hernán today | Photo: Carlo Vicente

STILL DRIVEN BY ART

“Well, I’m driven by the same desire that put me on a hitchhiking trip 10 years ago, but it’s the desire of following my true innermost impulses and also finding the resources to make them happen. I think that I don’t know any other language other than art making that can bring the best out of me. So that’s why I keep doing it.”

—HERNÁN