Episode

Highlights

LA LIMONADA

Juan García is born in Guatemala City. He and his ten siblings grow up in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city, zone 5, also called La Limonada. It’s cramped and tough, but his family is strong.

“Siempre papá nos enseñó a estar unidos como familia. Yo tuve que trabajar. Estudiaba y a los siete años tenía que trabajar… Había mucha pobreza, pero había mucha, mucha unión.”

Translation: Dad always taught us to stay together like a family. I had to work. I studied and at age 7 I had to start working. So, there was a lot of poverty, but there was a lot of unity.

—JUAN

Zona 5, where Juan grew up. | Photo courtesy of Paul Burkhart

A COUP IN GUATEMALA

On June 27th, 1954, the CIA stages a coup d’etat in Guatemala. Juan García is a toddler, but he remembers the years following the coup.

The heads of the Guatemalan military government with CIA agent in 1954

“Me recuerdo que los estudiantes de la universidad estaban orientando y a los campesinos pues al mente a los mayas sobre cómo defender sus tierras Luego comenzó la represión del gobierno militar, verdad.”

Translation: I remember that the university students were aligning with the working class poor. Like, the Maya people, to defend their lands. That’s when the repression of the military government began.

—JUAN

EL EJÉRCITO

As a kid from a poor family, Juan identifies with the mission of the students and leftists. He’s part of the pueblo. Sometimes, he’s part of the human mail. Sometimes, he and his brothers throw rocks at the soldiers. But he never feels too threatened by the military because he’s just a kid, and he’s in school. One day when he’s 16 or 17, he travels to visit his aunt in the nearby city of Escuintla, but he breaks a cardinal rule of living in a police state: he forgets his student ID. And he gets caught.

All 12 García family members. Juan is the last one on the right | Photo courtesy of Juan García

“Y en ese tiempo cuando los militares lo agarraban a uno era forzado el servicio militar. Si uno no tenía carnet de estudiante, se lo llevaban. Entonces a mí me agarraron en Escuintla y como no carga mi carnet de estudiante me agarraron al servicio militar obligatorio que era de 24 meses.”

Translation: And in that time, when the military caught someone, that person was forced into military service. If you didn’t have a student ID, they would take you. So, since I didn’t have my student ID, they forced me into mandatory military service, which at that time was 24 months.

—JUAN

MEXICO TO TEXAS

Juan and his friend desert their posts. But they’re caught and taken to a military judge. Juan and his friend serve 9 months of their 18 month sentence. It’s brutal. He doesn’t go into what happened, but he says he left with un monton, a lot, of problems. He thinks the only way to recover is to flee Guatemala and come to the United States, knowing he may never see his family again.

“Yo nunca me vine a los Estados Unidos por hacer dinero o algo sino que me vine por buscar libertad y encontrarme yo mismo.”

Translation: My reason for coming to the United States wasn’t to make money or something like that. I came to find freedom and to find myself.

—JUAN

IT WAS COLD, I REMEMBER...

After a year and a half of travelling, Juan makes it to Mexico’s Northern border. He’s ready. He hops in the back of a truck with other migrants. There are holes cut out of the sides for them to breathe in the desert air as they cross the border into Texas. It’s January of 1977.

“Había frío, me recuerdo. Y este muchacho que venía conmigo, en el México ya habíamos trabajado. Yo traía como $150 y él traía como $200. Llegamos a un bar donde estaban, había un partido de fútbol americano de los Dallas Cowboys. Dallas Cowboy eran tremendos. Y me dijo, “Mira,” me dijo. “Te voy a dejar $20, y estate aquí. Dame el dinero que tienes. Debo ir a buscar un apartamento y ahorita regreso.”

Translation: It was cold, I remember. And this guy who had come with me, we had worked together in Mexico. I brought about $150 and he had about $200. We arrived at a bar where there was an American football game on the TV. The Dallas Cowboys. The Dallas Cowboys were huge. And he told me “Look,” he said. “I’m going to leave you with $20. Stay here. Give me the money that you have. I’m going to go look for an apartment and come back in a bit.”

—JUAN

The friend never comes back. Juan stays in the bar until it closes. Nothing. Within Juan’s first hours in the US, he has no money, no friends, and no place to stay. He leaves the bar and finds a cardboard box. He places it behind a building and crawls inside. He sleeps there for 2 weeks.

“Perdí la confianza en persona ya mucho porque lo que él me hizo. Haber sufrido tanto durante año y medio y que se fuera y me dejara. Entonces fue como un choque va… Pero lo que me enseñó mi padre a mí a trabajar y la ansia de libertad de ser yo, de enfrentarme a obstáculos: comencé a salir adelante.”

Translation: I already lost my faith in people because of what he did to me. Having suffered so much during the year and a half and he left and left me. So, it was like a shock. But my father taught me to work, and the desire for the freedom to be myself and to overcome obstacles: I started to move forward.

—JUAN

SAN ANTONIO

Over the next nine years, Juan gets a job and starts a family of his own. He marries an American citizen, which gives him legal status, and they have two kids together, a boy and a girl. But the marriage doesn’t last. They divorce, and Juan feels like he needs to leave Texas. So, he reaches out to his brother, who’s immigrated to Providence, Rhode Island.

“Y le dije, ‘Mira, fíjate, no quiero estar aquí.’ Y él me dijo ‘Vente,’ me dijo.”

Translation: And I said, “Listen, I don’t want to be here.” And he told me, “Come here.”

—JUAN

CUANDO RESBALAS EN LA NIEVE

Juan gets used to Providence, even the snow, and rebuilds his life. He’s getting good at that now. He has his brother’s family and new friends. He earns enough money as a welder to find his own place. He goes through the motions, goes to church, even gets married again and has four more children. Six years go by. Everything is falling into place once more, until one cold, February night. Juan is at a bar on Manton Avenue when a fight breaks out.

“A mí me dieron 12 puñaladas ahí. Me asaltaron.”

Translation: I was stabbed 12 times. They assaulted me.

—JUAN

“Gracias a Dios estoy vivo. They put 36 staples in me, from here to there. Yo estuve 36 horas in critical condition, el mismo doctor me dijo, “Juan yo no sé. No fue la medicina la que te tiene aquí algo más. Pero sea lo que sea agradece.”

Translation: Thank God I’m alive. Because they had to put 36 staples in me. I was in critical condition for 36 hours. The doctor there told me, “Juan, I don’t know. It’s not the medicine that’s keeping you here. It’s something else. But whatever it is, be grateful.”

—JUAN

FATHER TETRAULT

“So I noticed you don’t often wear the typical Catholic priest garb. Why is that?”

—ANA

“That’s interesting. From the very beginning, I didn’t like wearing a clerical collar…I wanted to show the people that the priest is one of them. And they could, any one of them, could easily take my place.”

—FATHER TETRAULT

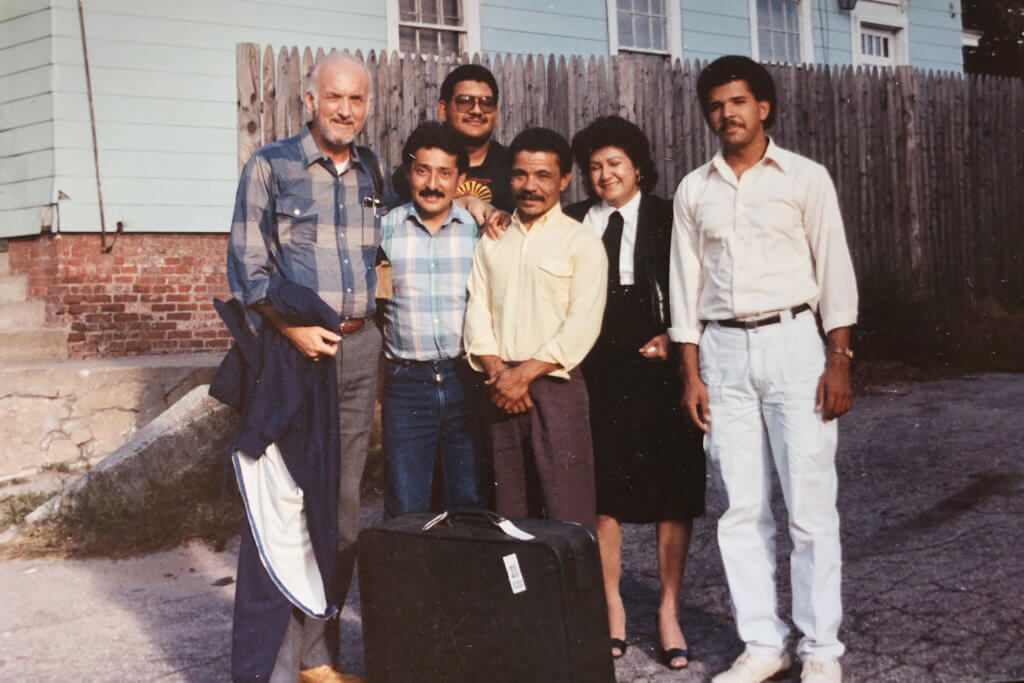

Father Tetrault (left) with a family from St. Michael’s | Photo courtesy of Father Tetrault

For the next thirty years, Father Tetrault leads Spanish-speaking Catholics both in church and on the streets. He holds the typical food pantries, clothing drives, retreats and bible studies, but takes it one step further and leads marches and fundraisers for grassroots immigrant activism throughout the country. It changes Rhode Island.

ANONYMOUS CATHOLICS

“Y él dijo en el sermón que nosotros éramos católicos anónimos y católicos pasivos. Que veníamos a misa, escuchábamos el sermón la palabra, verdad, Entonces nos íbamos a la casa y el lunes nos íbamos a trabajar, volviéramos a la casa. Abríamos una cerveza, presione a la televisión, y ya. O sea que no ponía nada en práctico de lo que habíamos escuchado. Y era cierto, porque así era yo. Eso pasó el lunes. El martes me quedó grabado eso.”

Translation: And he said in the sermon that we were anonymous Catholics, passive Catholics. That we went to mass, listened to the sermon, the word, and then we went home. And Monday we went to work, came back home, opened a beer, turned on the TV and that’s it. In other words, we didn’t practice anything we had heard. And he was right. Because that’s how I was. That’s what I did on Monday. On Tuesday, that idea stuck with me.

—JUAN

Juan goes back to St. Teresa’s that night to speak with Father Tetrault about what he can do, how he can be an active Catholic who carries out the word of God.

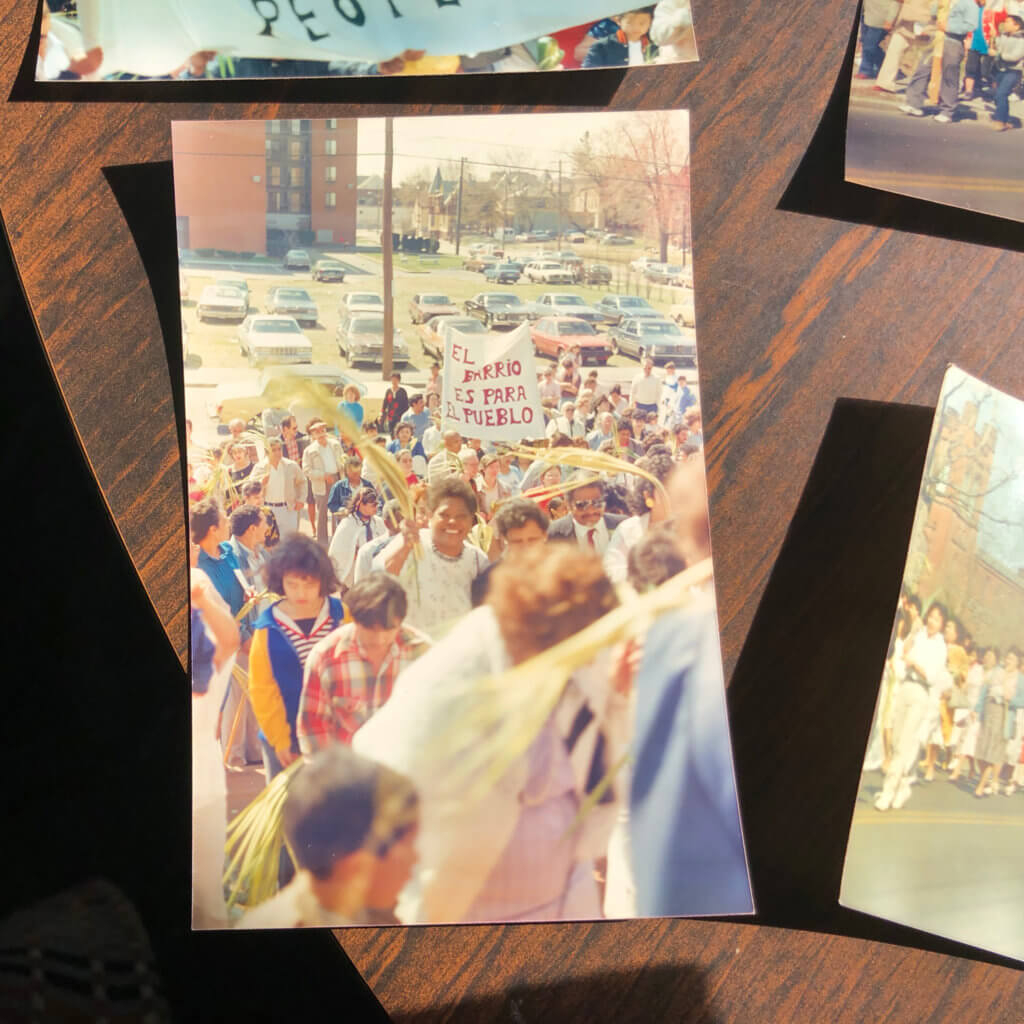

Father Tetrault’s active Catholic congregation in the streets of Providence | Photo courtesy of Father Tetrault

“Cuando yo entré él me dijo– yo no sé cómo sabía mi nombre, tal vez alguien se lo dijo o algo– pero cuando yo entré, estaba en una reunión. Él me dijo, ‘Juan. Bienvenido. Te estábamos esperando.'”

Translation: When I got there, he told me – I don’t know how he knew my name, maybe someone told him or something– but when I got there, he was in a meeting. And he said to me, “Juan. Welcome. We’ve been waiting for you.”

—JUAN

Juan’s story continues in Part II