Episode

Highlights

THE CHURCH

“La iglesia sigue siendo la iglesia, no importa si hay otro edificio para mí va a ser la iglesia. Porque aquí, aparte de trabajar, fue como que yo nací de nuevo.”

Translation: The church will always be the church. It doesn’t matter if it’s another building. For me, it’s going to be the church. Because, through work, this is where I was born again.

—JUAN

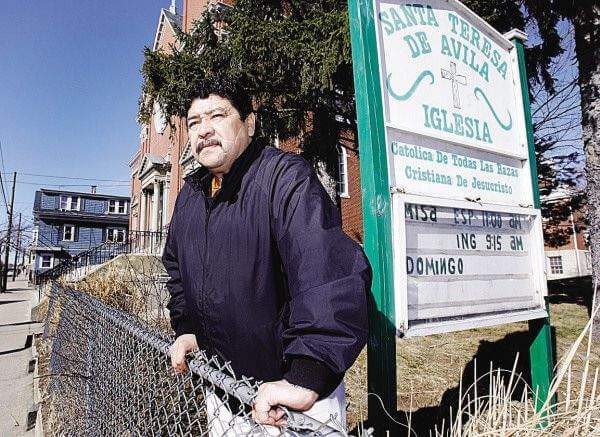

Juan in front of St. Teresa’s in 2009 | Photo: AP

Juan in the same spot in 2021 | Photo: Cheryl Adams Photography

ORGANIZING OLNEYVILLE

Father Tetrault offers Juan a job as part-time community organizer. Juan is elated. But he isn’t quite sure what that means. How does someone organize a whole community?

“Entonces el Padre me dijo a mí, ‘Mira, Juan. … te voy a poner un ejemplo. Mira, aquel, en la iglesia viene gente a traer una bolsa de comida y $5 y a la semana vienen otra vez. Tú tienes que hablar con ellos y saber porque ellos tienen que venir a poder una bolsa de comida y $5 y los demás no. ¿Cuál es el problema? Y siempre detrás de eso hay una injusticia. Tú tienes que buscar y platicar con ellos para ver cuál es la situación de ellos y organizarlos para que ellos cambien.'”

Translation: So the Father told me, “Look, I’m gonna give you an example. See, people come to the church to get a bag of food and $5, and the next week they come again. You have to talk with them and understand why they need to come and get a bag of food and $5 and others do not. What’s the problem? And behind this, there’s always an injustice. You have to search and talk with them to see what their situation is and organize them so that they can make a change.”

—JUAN

Now, with four kids, a good marriage and a new purpose, Juan has a home. He’s able to quit drinking and be a more present father and husband. And he helps others do the same. Through St. Teresa’s and Habitat for Humanity, Juan helps organize the purchase and renovations of dozens of formerly-abandoned houses in Olneyville.

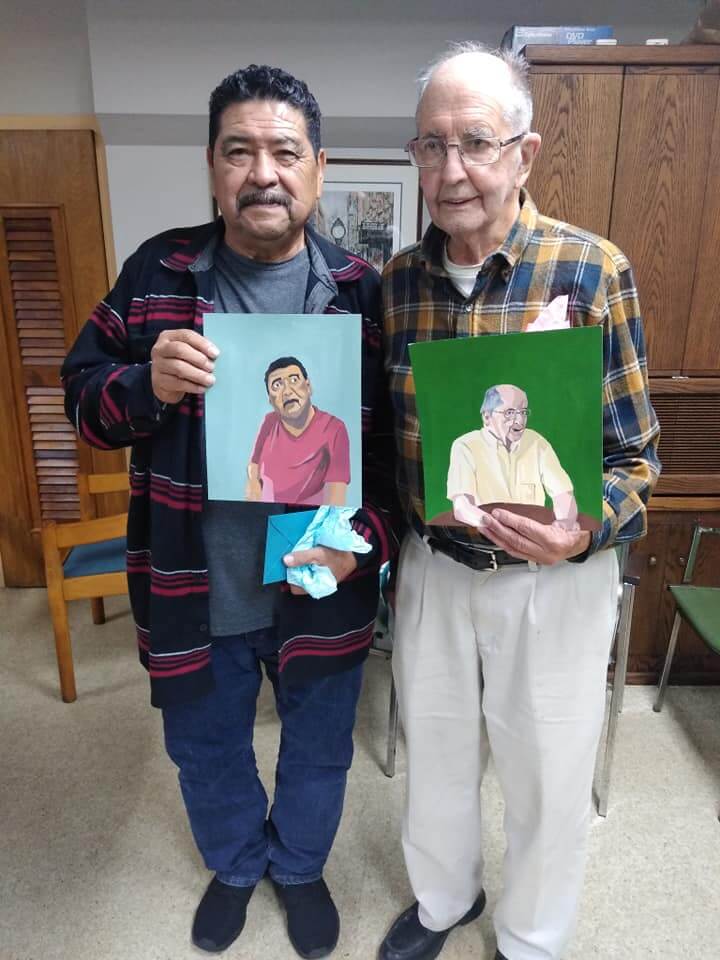

Juan and Father Raymond Tetrault in 2019 at a celebration of their work| Photo: Courtesy Juan García

COMO TÚ, HAY MILLONES

“Yo siempre he dicho que la persona que me cambió para mí completa la vida es el padre Raymond….pero una vez me dijo algo muy interesante. Entonces me dijo, nunca se olvida que él me dijo ‘Que vacío estás,’ me dijo. ‘Como tú, hay millones.’ Y ya no me dijo más, se acabó la plática.”

Translation: I’ve always said that the person who changed my life completely is Father Raymond. But one time he told me something very interesting. So he told me, I’ll never forget what he said, “How empty you are,” he told me. “You are one of millions.” And that’s it. He didn’t say anything else. The talk was over.”

—JUAN

“If a person takes his inner life seriously, he begins to ask ‘Who am I? What is this all about? What’s the purpose of life?’ Those are serious questions. And the church has a long history of people who also took those questions seriously….The church is a group of people who are searching, not that they have all the answers, but they’re seriously searching and they know, they need one another, to search together to find deep answers to life.”

—FATHER TETRAULT

“Entonces comencé yo a analizar estas palabras yo entendí, que como persona tenía que ver más allá. No solamente era por mí, sino que era por la comunidad.”

Translation: So, I started to analyze the words that I understood, how a person had to look outside of himself. It wasn’t just about me. It was about the community.

—JUAN

Juan decides to start his own group, El Comité de Los Inmigrantes en Acción, or the Committee of Immigrants in Action. It’s composed of 8 people at first, 8 latino immigrants from different countries. Juan García leads their meetings every other week in the basement of St. Teresa’s. They discuss the biggest issues facing immigrants over bowls of soup, under flickering fluorescent lights. And something that comes up time and time again is the ways people are being exploited at their jobs.

Juan leads El Comité in a protest in Providence| Photo: Courtesy Juan García

WORKERS’ RIGHTS

“Here you have people who are sitting ducks for exploitation…And there were a couple of real horror stories.”

—KAREN ZINER, former Providence Journal immigration reporter

Juan tries to help, so do the others at St. Teresa’s, but there’s only so much they can do as grassroots activists working out of a church basement. So, in 2000, Juan and Immigrants in Action plan a big, public event: they want to march on the streets of Providence and demand support for workers. They organize Rhode Island’s first-ever Worker’s Rights Day protest on May 1st, 2000.

“Lo que tienes que hacer es expandir esa esa semilla, y esa pequeña parte en la mente y en el corazón de la gente y sólo se logra eso organizándolos. Uno no puede ser líder, en lo que uno tiene que ser organizador.”

Translation: What you have to do is expand that seed, that small part in the hearts and minds of the people. And you only accomplish that through organizing. One can’t be a leader in this work. You have to be an organizer.”

—JUAN

“Para mí siempre Juan fue una persona muy amigable…siempre una persona muy preocupada por la comunidad…. Era más que todo, como un líder comunitario.”

Translation: To me, Juan was always a really friendly person, someone who was very worried about and focused on the community. He was, more than anything, a community leader.”

—HEINY MALDONADO

Juan and Heiny Maldonado at a protest | Photo: Courtesy Juan García

Soon, more grassroots groups form: English in Action, Workers United, a Rhode Island chapter of Jobs with Justice. And each year, the May Day march grows. On May 1st, 2006, that little march that started with just 50 people marching a few blocks, it grows to 28,000 marching nearly two miles, from Central High School to the Statehouse. Juan is one of the key organizers.

“Sí sentía emociones, me entiendes, pero emociones como de satisfacción que una persona que había hace un indocumentado, una persona que había salido de un barrio allá en la zona 5 en Guatemala, una persona que sufrió un montón de situaciones, había llegado a la mente ya la conciencia de cerca de 28,000 personas. ¿Cómo decir?”

Translation: And I felt emotion, you understand, but more like satisfaction. That a person that had been undocumented, a person that had left his neighborhood there in Zona 5 in Guatemala, a person who suffered a whole mess of situations, had touched the hearts and minds of close to 28,000 people. What can I say?”

—JUAN

POST-9/11 WORLD

“What affected people was there started to be these ICE raids. And they seem to be at times kind of random, you know.”

—KAREN ZINER

The first big one is the Michael Bianco leather factory in New Bedford. 361 workers are detained in one raid. [READ MORE HERE]

“There was something on almost all the time on talk radio, and it was divisive, and it was ugly. Calling undocumented immigrants, animals… cockroaches… diseases. All that kind of ugly, ugly stuff.”

—KAREN ZINER

ST TERESA'S CLOSES

Juan still attends mass every week and works out of a storefront in Olneyville. But it’s different.

“Osea que esta iglesia tiene historia. Aquí organizamos el barrio. Organizamos la comunidad. Encontré como una nueva vida. Encontré una forma de ser útil a la gente, a la comunidad y no solamente hacer una persona que pasa por la vida, verdad. Esas cosas tienen mucho valor para mí.”

Translation: This church has history. It was here that we organized the neighborhood. We organized the community. I found a new life. I found a way to be of use to the people, the community, and to not be a person who only lives for himself. Those things mean a lot to me.”

—JUAN

For Juan, St. Teresa’s will always be his church, even though the building has been abandoned since 2009 | Photo: Cheryl Adams Photography

NUNCA ME ENVEJEZCO

Today, Juan is 68 years-old. He says he’s retired, but he’s one of the busiest people I’ve ever met. He never turns down an interview. He still hosts his radio show over the phone during the pandemic. He had coronavirus and beat it. I mean, he never ever stops.

In addition to his weekly radio show and protests, Juan takes to facebook to get the message out about El Comité’s work | Video: Courtesy of Juan García

“Un día normal, iba a la casa y de repente ring el teléfono. Me dice, Juan, necesito irme el sábado a corte en Boston no tengo abogado, me puede llevar? Lo llevo….’Don Juan, mi hijo, el coyote lo tiene Nueva York, y no me lo quiere dar.’ Entonces yo voy con ellos allá y los rescato. ‘Juan mire me quedé sin carro mire mi trabajo si no me van a correr.’ Por lo llevo. Entonces esto es mi día. Es lo que hago todo el tiempo.”

Translation: A normal day, I’m at home and all of a sudden, my phone rings. They say, “Juan, I need to go to court on Saturday in Boston. I don’t have a lawyer. Could you bring me?” And I bring them. “Don Juan, it’s my kid. A coyote has them in New York and doesn’t want to give them to me.” So, I go with them to New York to rescue them. “Juan, my car broke down and I can’t get to work. So, I take them. This is my day. This is what I do all the time.”

—JUAN

“¿Y te gusta? ¿Te gusta tu trabajo?”

Translation: And do you like it? You like your work?”

—ANA

“Me encanta porque a pesar de los años que tengo que en lugar de estar ahí sentado, retirado, soy útil. Es lo más importante. Sabes por eso no me envejezco [laughs] Tal vez lo único que sí quiero para todos que van a escuchar esto: no importa como sean, quienes sean, lo que han sufrido. Sólo recuerden sé algo. No solamente vivimos para comer y para tener y almacenar. Vivimos para desarrollarnos y desarrollar a los demás.”

Translation: I love it because after all of these years here in this place, I’m retired, but I have a purpose. That’s the most important thing. You know, that’s why I don’t get old [laughs]. The only thing that I want everyone who’s going to listen to this to know: it doesn’t matter how they are, who they are, what they’ve gone through. Just remember to be something. We don’t only live to eat and to have and to hold on things. We live to grow and help those around us grow.”

—JUAN

Ana and Juan for a quick, unmasked moment | Photo: Cheryl Adams Photography