Episode

Highlights

BORN IN CAMBODIA

“I mean, I born here. Yes. But I was raised and grow in the United States. I can’t go back. I can’t do anything, you know, and what can I say, you know, I gotta tell myself that this is me now. I’m Cambodian now, you know?”

—POV

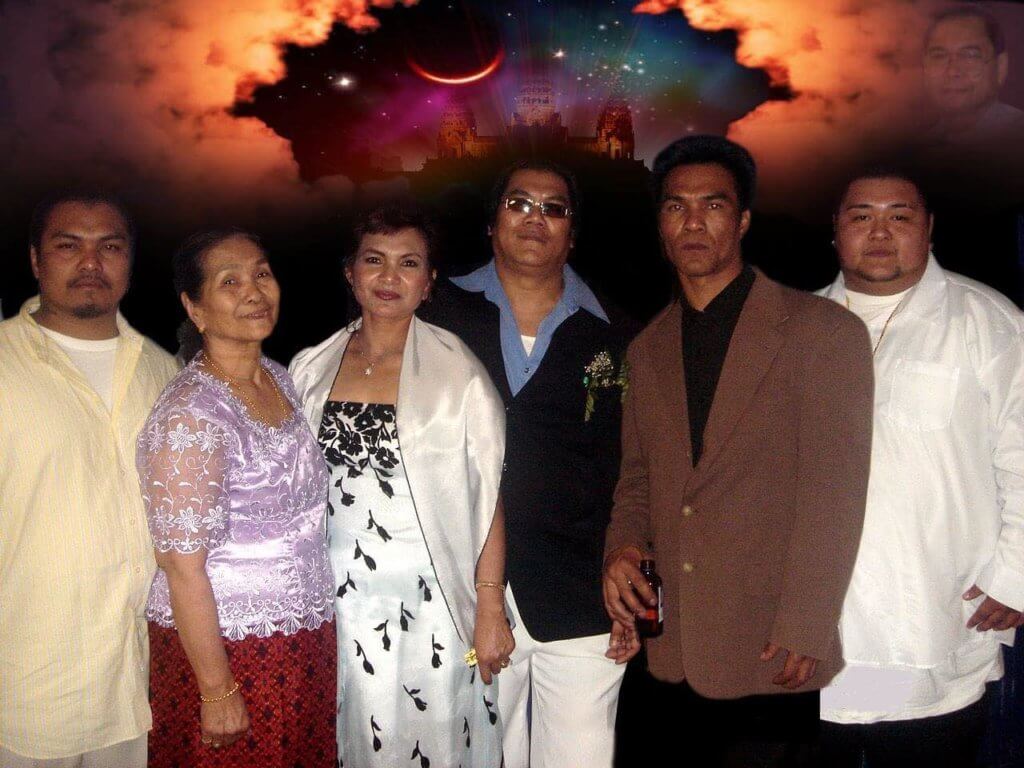

Last time Pov Pech was in Cambodia, he was six-years-old and dodging bullets. Last summer, after 40 years in the United States, he was deported back to a country he barely knows, leaving his family and his American identity behind.

Pov in Cambodia | Photo: Pov Pech

MEKONG RIVER

This is the second time I’ve interviewed Pov Pech. And while coronavirus has made meetings and interviews via video chat the new norm, I’m interviewing Pov in the before times, at the beginning of 2020, back when it was rare to do extensive interviewing not in person. I’m in our studio in Providence, Rhode Island. And Pov is sitting outside of his apartment in Phnom Penh on the banks of the Mekong River, which divides Vietnam and Cambodia.

“I never consider anybody friend because I have a hard time to trust people now, you know…”

—POV

Each time we talk, Pov tells me how lonely he is in Cambodia. Back in Massachusetts, he has a big, close-knit family. They lived and worked together and would spend most of their free time eating their mom’s cooking in someone’s backyard. Now, Pov still relies on his family for financial support, but he passes his time alone.

Pov (left) and his family back in Lowell | Photo courtesy of Pech Family

JANUARY 16, 1990

January 16, 1990. 16-year-old Pov and his friend, Dyna, bring guns to the courtyard of Central High School in Providence and open fire.

“I had never heard of someone just randomly shooting children at a school. It was big. It was before Columbine….These kids didn’t go through the normal upbringing that citizens who give birth to children here go through. This is war-torn refugee camp, or whatever. It happens. You can understand why someone might be that way. Doesn’t mean they shouldn’t go to jail if they do something wrong.”

—DAVID MOROWITZ

Emergency response at the scene | Photo courtesy of WJAR

ESCAPING THE KHMER ROUGE

“My first memory is I think when I was young. And I think it was in Khmer, Cambodia. And I know I was running around naked, with no clothes on.”

—POV

But it’s more serious than he’s letting on. Pov Pech was born in 1973, two years before the Vietnam War would end and throw Cambodia into the genocidal reign of the Khmer Rouge. The Khmer Rouge wanted to start over, wipe out any trace of the West and turn Cambodia into a rural, Communist utopia. They began by emptying the cities. The middle class, the intellectuals, and the religious were targeted and killed. Then, they set up work camps. Young boys were taken from their families, stripped of all of their identity and clothing, beaten, and forced into manual labor. Pov was one of these boys. He was taken from his mother when he was five-years-old.

“Back then, I couldn’t really understand what’s going on. All I know is just that people screaming and people running, scattered everywhere. It’s all like flashbacks, stuff, you know, memories come back. I be having dreams, you know. I be having nightmare dreams about it.”

—POV

Cambodian child labor brigade | Photo: Documentation Center of Cambodia

THAILAND TO THE BRONX

“She used to tell me the story. She said that she doesn’t care what the perception is coming to the United States, as long as all her kids come with her. Safe, come with her. Than being over there. She doesn’t care what was ahead of her. As long as all her kids and herself and her husband are safe together. She just willing to come, and then she adapt to it.”

—BORI

They arrive in the South Bronx in January, 1981. The family of 6 are placed in a one-bedroom apartment… Pov’s stepfather is able to get a job as a cook, but money is tight.

“I started stealing when I was in New York. Because I was hungry…”

—POV

Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1980s | Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

CAMBODIAN IN LOWELL

“Out of the brothers, he was the one, the roughest one, you know? The old mindset.”

—BORI

“A lot of the Cambodians, they didn’t want no problems and stuff. And I’m the one that end up stepping up and stuff. And I start having issue with them. And when they see that, they don’t like it, so I guess they got me on the radar. So every time they see me, they always trying to like, jump me, and stuff like that. And I started get upset or mad. And I started, like, bringing weapons to school, you know, like, I’d be making all kinds of nunchucks and all that stuff. Just to protect myself, and what I need to do.”

—POV

When Pov is 15, he’s sent to a juvenile detention center in Lowell.

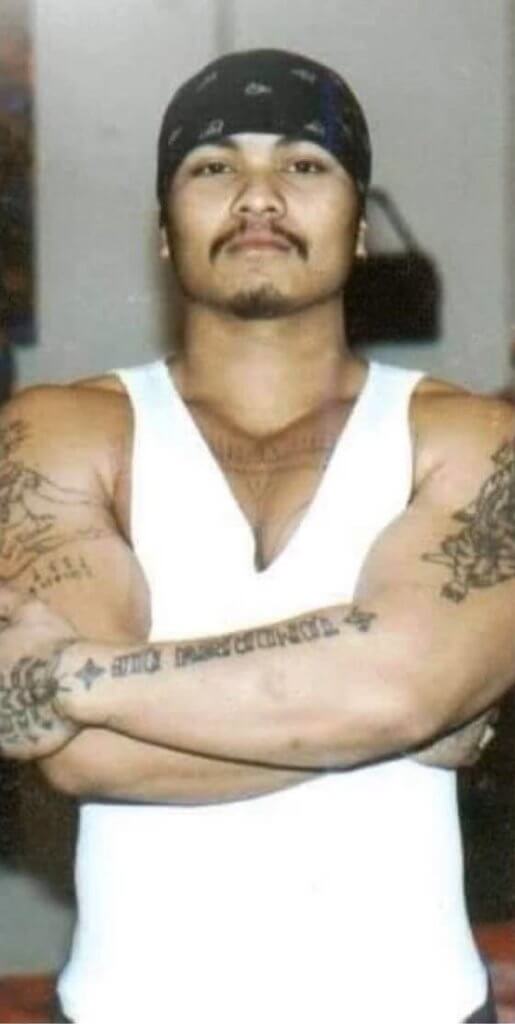

Pov describes having flashbacks to being in Cambodia. Nightmares about gunshots and screams that would keep him on edge. Even though he’s scared on the inside, on the outside, he’s tough. He starts to make friends with the other Cambodian kids locked up with him. A couple of them are from Providence. After he serves his short sentence, he’s released to a halfway house in Lowell under the state’s custody. Whenever he gets a chance, he sneaks down to Providence to hang out with his friends.

Police think Pov is older than he is because of his tattoos and his hardened attitude | Photo courtesy of Pov Pech

CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL

“And I met a girl… And she go to Central High School. So I used to walk her back and forth to go Central High School. And that’s when it happened again. That situation.”

—POV

He claims that a group of students are harassing his girlfriend and other Southeast Asian students for being Asian. They’re throwing out racist slurs, laughing at their accents and names. They don’t realize who they’re messing with.

“What happened, when I walk over there, they all walk toward me. I think it was around lunchtime. And then I started to pull out the gun and I started shooting at the air. Then suddenly, they was running everywhere. When they run inside of the hallway stuff, I went in there, and I shot, and I guess I hit the wall, and ricochet and hit the girl in the shoulder.”

—POV

The bullets hit one student in the back and another kid, a recent graduate visiting campus, in his leg. They are taken to the hospital.

“I guess after that, I fled. I ran. I had a gun in my hand, and I ran, and this guy was chasing after me, and I jump over the fence.”

—POV

Watch news clips from the day of the shooting, the aftermath, and the trial | Video courtesy of WJAR

TRIAL OF POV PECH

“The prosecutor outlined what the all-white jury would hear…”

—WJAR NEWS CLIP, 1991

“You’re going to hear about students panicking, fleeing in terror. Some running down that staircase I’ve just spoken about, some students jumping over the wall…”

—DAVID MOROWITZ, FROM WJAR NEWS CLIP, 1991

Pov is still illiterate. He speaks better Khmer than English, and there’s no translation available to him throughout the trial.

“You know, I was like 16 and a half and 17 and I didn’t really understand or know what’s going on. Because I believe in that when somebody is your lawyer, they represent for you, so they’re gonna work for you and do for you. I put everything, my trust towards the lawyer, but I still don’t know what’s going on, what’s the rule, the law, about the court system. I don’t know anything about that.”

—POV

“And it may have been true that the students at the school were calling him and his friends monkeys. It may have been true. Shame on those students. It just didn’t apply. This was just a bad kid who did, he did something bad. Just that simple. And that was the extent of it. So I think we have to be hard on those that threaten the rest of the community and interfere with the kind of system and the kind of society we like to have. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That gets imposed upon when you get a bullet in your back for no reason at all. It’s not a self defense case.”

—DAVID MOROWITZ

Pov just wants to go in, serve his sentence, and get back out. But it’s not going to happen that way. This will follow him for all of his life.

“I just don’t want my son to go through what I go through, you know. I just want him, you know, to be somebody. To be something. I can’t do anything right now, I’m just happy that I’m still living, still breathing. And I can live another day to still talk to my son and my mom, you know?”

—POV

Pov in Cambodia | Photo: Pov Pech

Episode

Resources

Forced Labor and Collectivization from United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Cambodian Information Center (CIC)

Cambodian Genocide Program from Yale University