Episode

Highlights

Being in Cambodia

“And I just remember just being around a lot of Cambodian. Not that much of, you know, other ethnicity. When you walk all you see your own, you know, race, you feel warm. Instead of other cultures looking at us and looking at us weird. And then you feel, like, insecure.”

—BORI

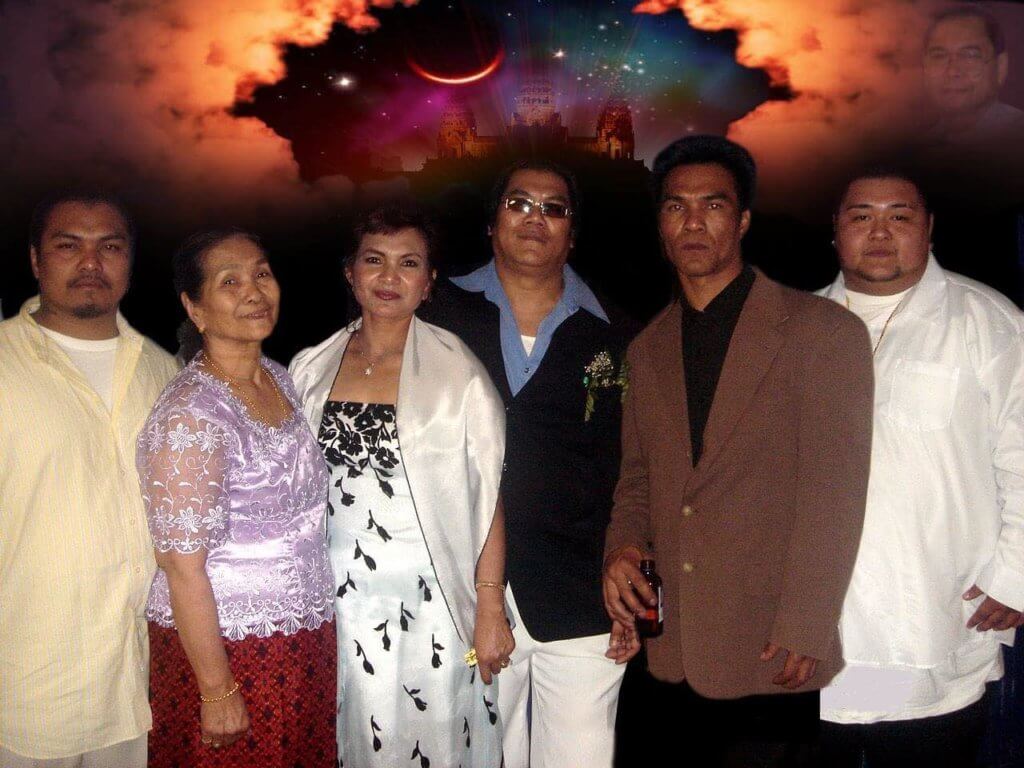

The Pech Family | Photo courtesy of Pech Family

Doing time

“Everybody was shocked because we didn’t know that he was gonna be in that route. Doing that situation. We don’t know what trigger his mind.”

—BORI

Together with the trial and the actual sentence, Pov serves roughly 6 years in prison. When he’s released, he doesn’t tell anyone. He takes a bus from Cranston, Rhode Island to Lowell, where he walks to his mother’s house, and knocks on the door.

“I don’t think I was like, learn my lesson or anything because to be honest with you, to be truthful, because I was raised and grow up in jail.”

—POV

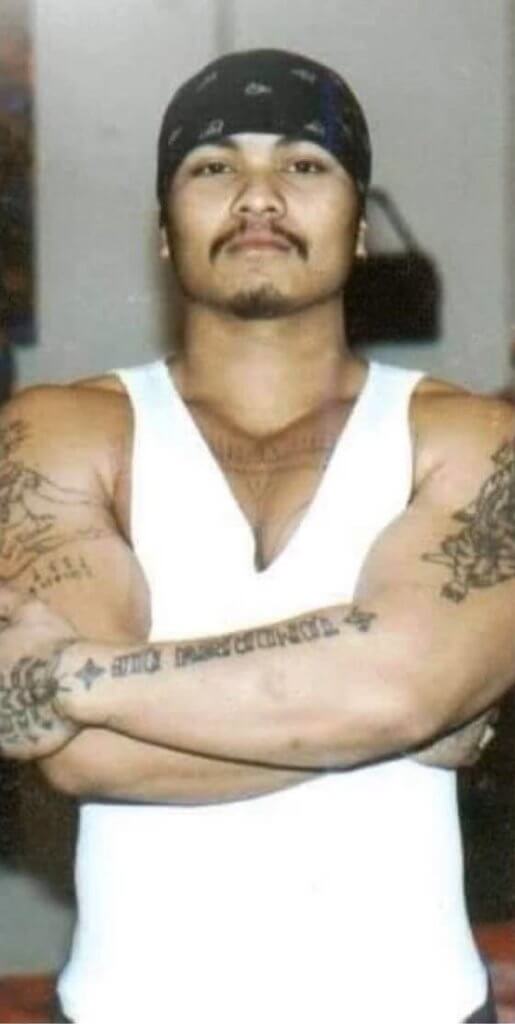

Young Pov | Photo courtesy of Pov Pech

Hustling

How much money were you making selling drugs?

“It depends on, like, people, stuff like where they come up with money. Probably like 50 dollar or 100 dollars. A day.”

—POV

“Growing up in Lowell, all the brothers was known as gangs. If one got in trouble, the whole police know the other brothers, so the police will pick on them.”

—BORI

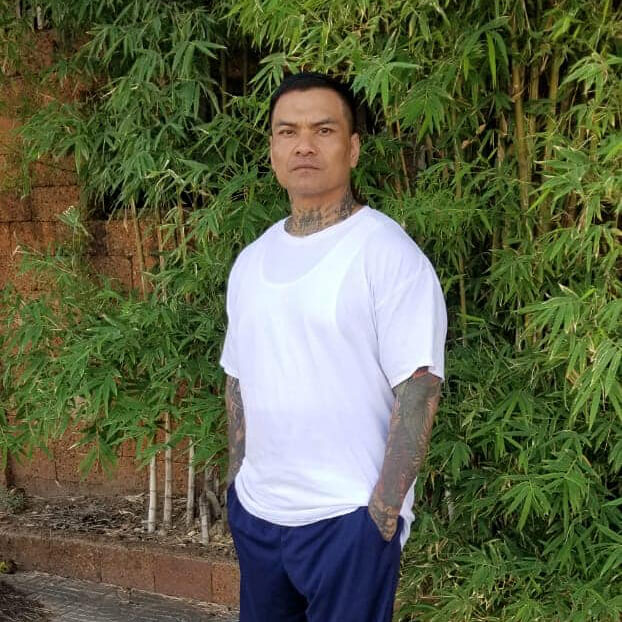

Bori and Tony | Photo courtesy of Pech Family

Ordered Deported

9/11 changes the entire US system of immigration. The Bush administration shifts the government’s focus from letting immigrants in to kicking immigrants out. In 2002, the United States signed a repatriation agreement with Cambodia. For the first time, the US could now deport Cambodians living in the US back to Cambodia, if they had legal grounds. So, after four years out of prison, Pov gets picked up by immigration.

“They brought me to Hartford Connecticut Immigration, the holding facility. And I remember that they came and talk to me. It was me and it was a couple Cambodian, a couple Vietnamese people. And they came to talk to us and talk to me, really. They telling me that ‘Listen, if you sign the paper to go back to your country, once you sign it, and if they don’t take you back in 90 days, they have to release you unsupervised.’ So I did it. And everybody did that.”

—POV

“They go about their lives after they’ve been detained and/or deported in the same way that you or I would, except they had to check in with ICE. Especially when they’re doing it for like 20 years, it doesn’t strike them as like, ‘Oh, I’ve been ordered deported.'”

—BETHANY LI, IMMIGRATION LAWYER

Tony Pech advocates for deportation reform | Photo courtesy of Pech Family

Highs and Lows in Lowell

“The whole police station in Lowell, they know me. The whole police station in Providence know me. Probably I’m the first one, my name come up. Even though it was not me, you know?”

—POV

“I remember when he was born, he call us right away, middle of the night, saying, screaming, “He’s here! He’s here!” And then he texts us a name. He was like, “Should I name him Cobra? Because he born on the year of the snake.”

—BORI

Pov with his son, Anthony | Photo courtesy of Pov Pech

Framed

“But the things that I saw that day it was just, like, unbelievable. Just can’t be his, you know?”

—BORI

“And I got framed. Because there’s a case that there’s a robbery and with the police and the witness testified. Re-read the record and everything.”

—POV

Pov in Cambodia | Photo courtesy of Pov Pech

Still in Survival Mode

“When I went back to New Hampshire and they say, “Oh, yeah, they got your travel docket. You going back.”

—POV

“I don’t know anything about Cambodia. United States, that’s my country. I lived there for 40 something years. You know? And then you drop me off here like you dropped me off in, like, an island that, you know, you have to survive.”

—POV

Pov feels unsafe as someone who’s visibly American in Phnom Penh. His tattooed body and Nike sneakers signal to every Cambodian who sees him that he’s a deportee. And that’s a sight that’s become more and more common in Cambodia since President Trump took office. From the repatriation agreement in 2002 up until 2016, 750 Cambodians were deported from the US. In the past three years, that number has increased exponentially. Between 2018 and 2019 alone, Cambodian deportations increased by 280%. The total number of deported Cambodians is now in the thousands. Almost all are refugees.

“I just want someone who is working on behind all this deporting just to dig more into the family situation. More reasonable, you know, reason to get this person deported.”

—BORI

Tony and Pov’s son, Anthony, after Pov has been deported | Photo courtesy of Pech Family

Episode

Resources

Forced Labor and Collectivization from United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Cambodian Information Center (CIC)

Cambodian Genocide Program from Yale University