Episode

Highlights

A coronavirus Ramadan

“We used hold, like a mass iftar. A lot of people come together to break the fast together. Which are now a little bit less possible.”

—AMJAD

Since coronavirus hit, [the mosque’s] doors have been closed, even during Ramadan. Normally, during this month, Muslims head to the mosque to pray after breaking their daily fast with a huge gathering of friends and family called an iftar. But this year, even the iftars have changed.

“For me, this Ramadan is the first Ramadan that I’m really enjoying it. Really. Because we are home.”

—MAYSS

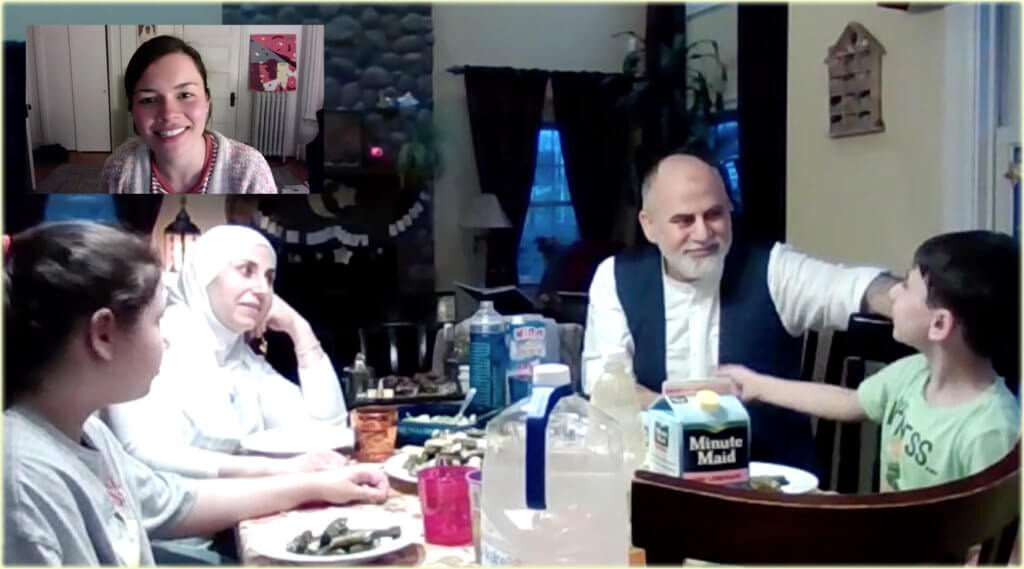

Breaking fast via Zoom

The pandemic has made video chatting a way of life. So, I’m able to virtually sit at the table with the Kinjawi family and break fast with them throughout Ramadan without having to leave my home.

“And that’s the purpose of the fasting: so you might achieve piety. When you look at what the fasting is supposed to teach us, or to make of us, you find that it’s just purification of the human soul into a better one. You need to be kinder to people, you need to think of your neighbors, you need to think of those who might be fasting by choice, but there are people who are fasting because they don’t really have the means to not fast.”

—AMJAD

Inside the Kinjawi home | Photo: Cheryl Adams

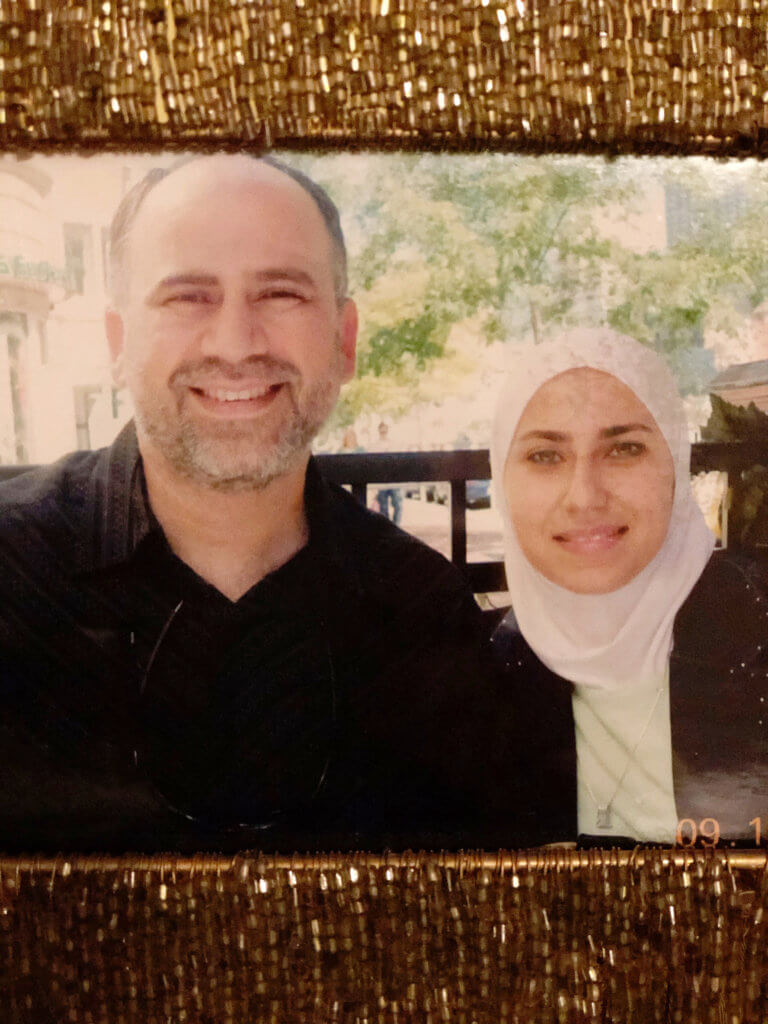

Sitting with Amjad | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Growing up in Syria

Amjad’s family is Muslim, and his parents teach their kids about Islam, but Amjad does not have a deep, spiritual connection to the religion. He’s more into education and becoming a dentist. He attends university and dental school in Damascus. Then, he travels to France to learn more advanced practices to bring back to Syria. But along the way, he takes a trip to the United States that makes him question going back to his home country to practice dentistry.

9/11 for a Muslim-American

“That is not Islam. That is something where sometimes the media can go a little wrong by exposing the negative, even though it does not represent the true religion and say, ‘Okay, this is what it is. This is who we are dealing with. All Muslims are like this.’ I’m not gonna be ashamed of a fanatic or somebody who’s crazy, who would like to, in the name of Islam, do something evil. I’m not associated with this person. This person is not associated with my religion. So I don’t even know why I should be ashamed of him.”

—AMJAD

Mayss Bajbouj Kinjawi | Photo: Cheryl Adams

On the other side of the Atlantic

“I born in Algeria. I had a life in Algeria. I came to Syria for a while. I went to France. So, my life is always in change. And May Allah forgive my parents, they didn’t teach me the religion. So I start teaching myself. I start looking around me and why this is happening, why this is happening. So I tried to teach myself and to know about Islam more.”

—MAYSS

After 9/11, France erupts into rallies and protests against hijabs. It creates a hostile environment for Muslims, especially covered women.

“Ramadan came. And I had the moment for me because I was ready to put my hijab….And I decide to put it, and I put my hijab. And one of my friends said to me, ‘Mayss, are you crazy? You should do the visa first before your hijab. And now with your hijab, no one is going to accept you.’ And I said to her, ‘You know, I don’t believe that. Because if you do something truly for God, and if God has a plan for you to go to United States, I’m going to have the visa. It doesn’t matter. The hijab or not.’ … And I went to the interview. And I remember I was in the room. There were a couple of people that are denied, and I’m only one with the hijab. I was accepted.”

—MAYSS

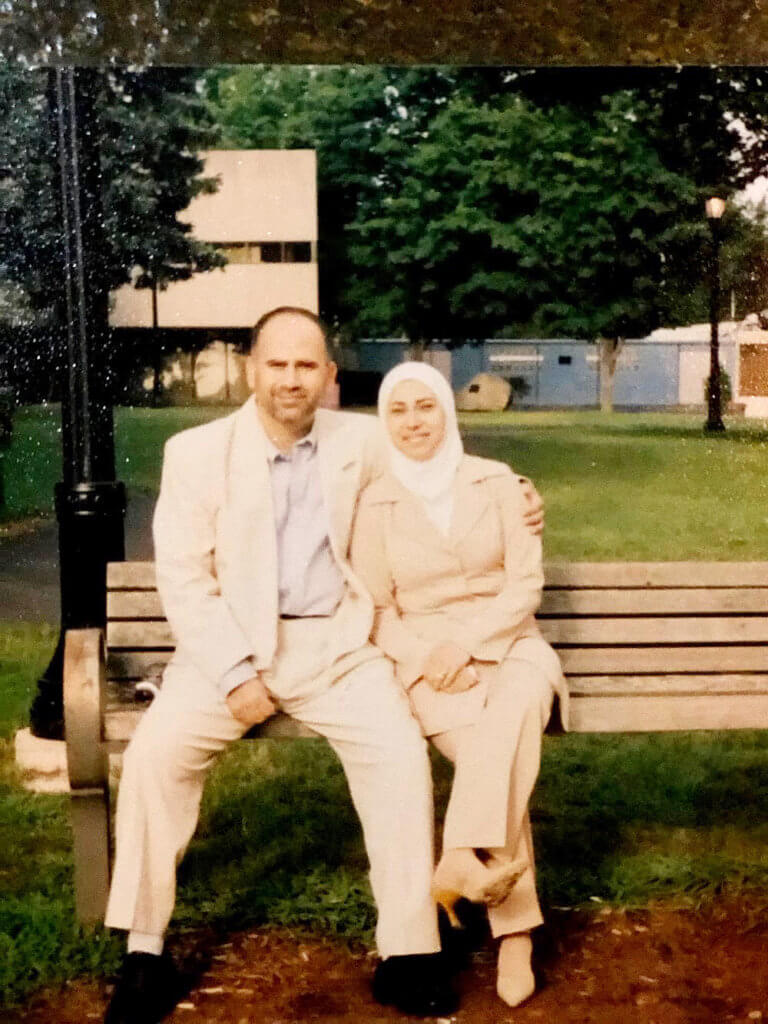

Amjad and Mayss on their wedding day in 2003 | Photo courtesy of Kinjawi Family

The Kinjawis got married in Syria and the United States | Photo courtesy of Kinjawi Family

Moving to North Attleboro

Mayss gives birth to Lujayne in North Attleboro. And soon after, Mayss begins to get work at local universities. One of her first jobs is a professor position at Boston College, a largely white, Jesuit school in a wealthy suburb of Boston. She is the only covered woman on campus.

“After two years, it was for me a first time seeing a covered woman inside the campus. When you go in, of course these people they kinda look at you saying, ‘Oh, she’s Muslim.’”

—Mayss

Lujayne at the kitchen table | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Syrian identity during civil war

I’m just wondering, like, how you talk to your kids about Syria, like being immigrants, people who came before what’s happening in Syria now…. And how do you tell your kids about that? You know, like how does that affect you feeling connected to Syria as a country?

“When the regime has attacked one of the cities with the chemical weapons… and the scenes: they’re still vivid in my head, the scenes of children suffocating because of the chemical weapons that can be used. That sometimes I see my children in those kids. And you wonder how you’d feel if it was your child that’s in front of you that is suffocating.”

—AMJAD

They bring Lujayne and Zayd to rallies against anti-semitism and islamophobia. And that’s a big part of how the Kinjawis relate to Syria now because they don’t see themselves returning for a long time.

Lujayne and Zayd in the backyard | Photo: Cheryl Adams

End of Ramadan

How do you guys feel at the end of Ramadan?

“I personally can’t believe that it’s done.”

—AMJAD

“I feel it’s one of the best Ramadans that I’ve had…Ramadan comes always with a lot of spirituality…Living Ramadan and leaving Ramadan will probably help us more to know exactly what we want after, especially that we are still in quarantine, especially that nothing changed. But we changed inside.”

—MAYSS

“Each Ramadan you are elevated to a step…So it’s almost like a ladder. Each Ramadan is one of the steps on that ladder. And the top of the ladder is where you are at your purest, at your finest, at your ‘bestest’, as Loujain used to say [laughs].”

—AMJAD

Amjad and Mayss at home | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Syrian-Muslim-American

“So we are building two things: the social, the community, and being American with all the values that Muslim and Islam can bring to that, teaching our kids…I want them to be proud, happy and citizens here. We are American at the end. So no matter what we are, we are here, we are living here, and we are doing our job here, we are serving people here. Our community’s here. So we are part of it.”

—MAYSS