Episode

Highlights

Práctica de bateo

“¿Cómo describiría el juego de béisbol? ¿Qué le digo? Dentro del terreno de béisbol, tu encuentras muchos amigos que, más que tus amigos, son tu familia. Te enseña mucho sobre la disciplina, el respeto, y enseña a disfrutar lo que tú haces.”

Translation: How would I describe the game of baseball? What can I say? In the world of baseball, you find a lot of friends who become more than friends. They’re family. It teaches you a lot about discipline, respect, and it teaches you to enjoy what you do.

—ARTURO REYES

“Me gustaría the University of Rhode Island. I would like. But I don’t know…De verdad, sí, un poco difícil porque no estamos seguro de si vamos a jugar o no. Entonces, si no jugamos, habría menos oportunidades de que me vean, y que algún coche me reclute.”

Translation: I would like the University of Rhode Island. I would like. But I don’t know. It has been a little difficult because we are not sure if we are going to play or not. So, if we don’t play, there will be fewer opportunities for people to see me, and for a coach to recruit me.

—RUBEN OGANDO

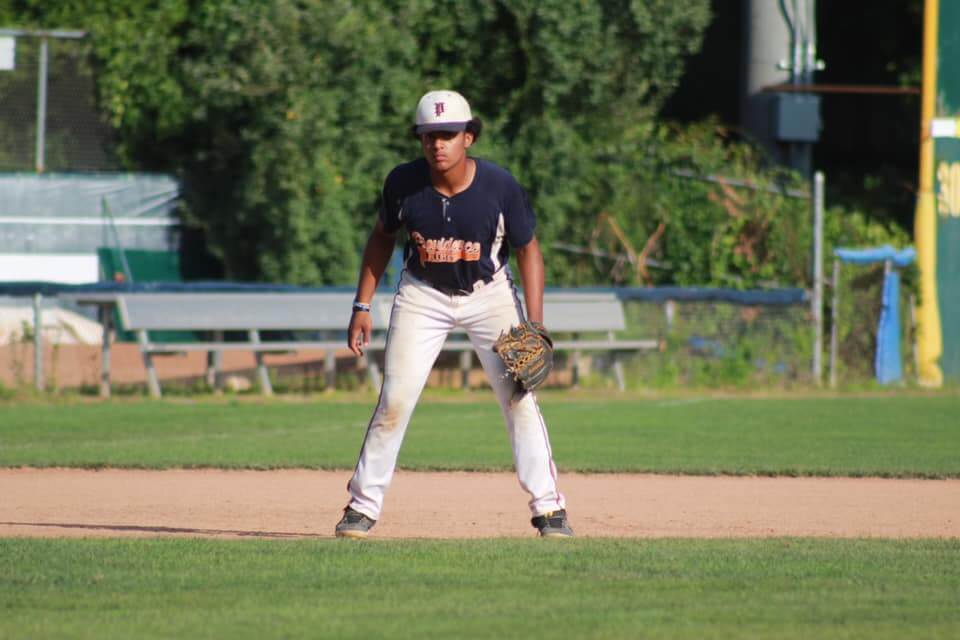

Ruben loading up to take a cut at batting practice | Photo: Ana González

The pandemic has changed everything in the world of competitive youth sports. It modified practices, canceled games, and made the college recruiting process more unknown.

“It has been tough for the seniors because everything is at a standstill. A lot of the college players redshirted. What that means is they have an extra year of eligibility. So that hurts seniors, juniors. It hurts everybody down the line.”

—FRANKLIN SALCEDO, HEAD COACH OF THE 18 AND UNDER TEAM

DOMINICAN BASEBALL CULTURE

To understand how Dominican baseball culture has been transplanted from its Caribbean home to this small New England state, you need to get to know Kennedy Arias.

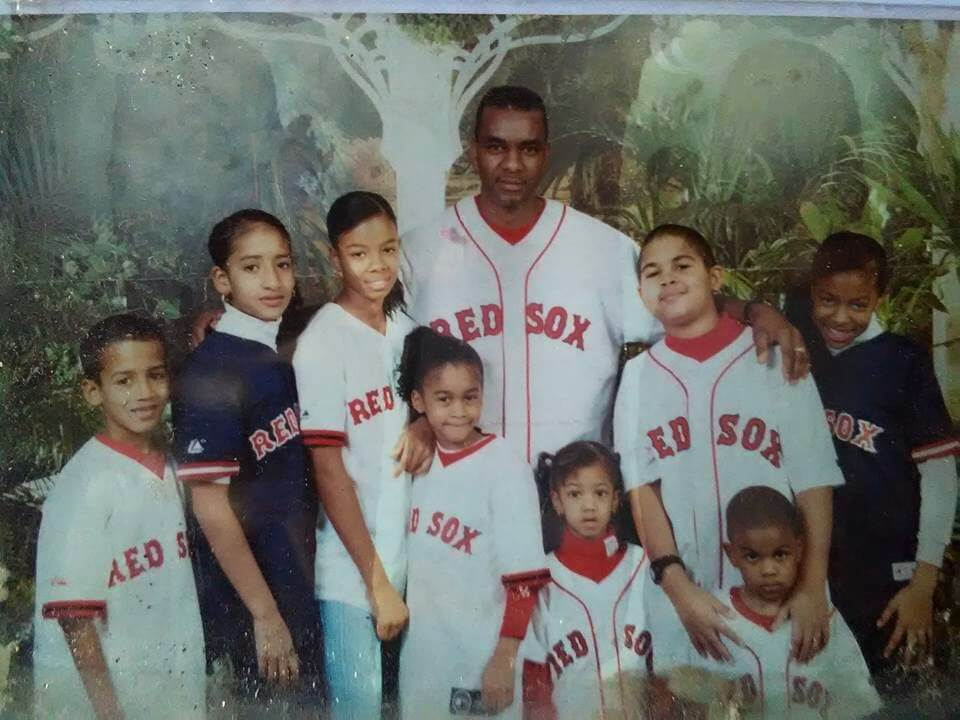

Kennedy Arias and his family in the early 2000s | Photo: Courtesy of Kennedy Arias

“I started with Roberto Clemente little league. I want to be, like, volunteer. My son play in this league, and they need coach.”

—KENNEDY ARIAS

Since the 1990s, the Dominican Republic has become a hotbed for Major League Baseball stars. The island nation has produced more MLB players than any other country outside of the US. Every single MLB team has an academy on the island where they recruit and sign teenage players.

AN ODD PAIR

“And something that I see over here is that you have everything. The kids have, you know, opportunity to do what they want to do. And something that I try to be, not just a good coach. I want to be a good mentor. You know, some people need motivations to them, and to explain to them, you know, how important it is to have education and to play any sport.”

—KENNEDY ARIAS

“One day, I … looked out the back window. It’s overlooks Mary Fogarty …And Kennedy was out there with like, way too many kids by himself. Obviously, he didn’t have the resources, he didn’t have additional help… And I just one day, I went down there, introduced myself and just, kind of, things took off from there.”

—BILL FLAHERTY

Kennedy and Bill are an odd pair. They’re both so deeply entrenched in their worlds that they probably would never have even met if it wasn’t for baseball. But they both know that there’s untapped potential in these kids. And while Kennedy knows the community and the culture, Bill knows the world of competitive youth sports.

BUILDING PSL

Youth travel teams are big business. Plain and simple. The teams that Bill suggests playing come from the wealthiest towns in New England, where families easily spend 3,4, sometimes $5,000 for a single summer of training, travel and tournament fees. That’s just not possible for the players Kennedy has been coaching. So, they begin to fundraise. They raise tens of thousands of dollars that first year. By the summer of 2007, they have more than enough to cover the costs of equipment, facility rentals, travel and tournament fees. Soon, New England gets to see what Providence Sports and Leadership can do.

“I spent a lot of time eating pastelitos, rice and beans in people’s kitchens trying to build up credibility and trying to get them to trust me…But then families and kids start to get it. They understood what we were trying to do.”

—BILL FLAHERTY

“My goal now is not help kids to go to play prof. Not really really. My goal is maybe, you know, combine education and the sport to try to get a scholarship.”

—KENNEDY ARIAS

COLLEGE BOUND

PSL gets players recruited to Wheaton College, University of Maine, Brandeis University, University of Rhode Island, Johnson and Wales, and a handful of other programs. To this day, they’ve sent close to 50 kids to college to play baseball. Most on scholarships.

Franklin, Kennedy, and three PSL players share a joyful moment after signing their letters of intent | Photo: Courtesy of Kennedy Arias

“I’ve never been more proud to represent a group of kids in whatever form that may be. If we’re sitting in a classroom talking to different college coaches about the college experience in college baseball or out on the field in a tournament, or what have you, but it’s totally changed my life.”

—BILL

Former PSL players pose in their college uniforms | Photos: Courtesy of Franklin Salcedo

CULTURE CLASH

“My team, I love when they’re loud. I love when they’re cheering and stuff like that. And that can be very intimidating to others, especially, you know, other communities that are not used to that. Like we have guys with, it’s an instrument called the guïra. We have a tambora. We bring speakers, like, we like to have fun, you know, because we work so hard.”

—FRANKLIN SALCEDO

PSL players having fun at the University of Maine | Video courtesy of Franklin Salcedo

Sometimes, it’s just weird looks when the guys yell Spanish cheers or bump bachata on the speakers. Other times it’s more serious.

“Race is often front and center with the way people interact with us, the way they see our program…. And I’ll never forget, we were playing in a tournament,…and I was over coaching third base, and the other team’s dugout was right off the third base side, and they said, ‘Oh, what’s Providence Sports and Leadership?’ And some kid said, ‘You know, it sounds like a good landscaping company.’ And I could tell right away exactly what they’re talking about.”

—BILL

The PSL Tigers win the game | Video courtesy of Franklin Salcedo

“Somebody will miss practice and they’ll come back the next day, I say, ‘Why weren’t you a practice?’ And they say, ‘Oh, I had to go to the doctor with my grandmother to translate for her.’ ‘Why’d you miss the game or the practice?’ ‘Oh, I had to go work.’ And another thing that came up: I remember Franklin said, ‘Bill, I got this problem. I got this kid, he’s out on the street, his family just got evicted, like, what do we do?’ And I don’t know. Those are things that I just–You know, I know the game of baseball. I know how to coach it pretty well. But that’s such a small part of what we’re doing here.”

—BILL FLAHERTY

LAVISH LIFE

“My dream is to become a professional baseball player and play baseball in college and do the most that I can to make it there. PSL, they’ve been helping me a lot with getting me out there. We’re talking to a couple colleges…So we’ll see from here what goes on.”

—SALOMON LLUVERES

Senior captain and third baseman, Salomon Lluveres, wants to become a professional pelotero | Photo courtesy of Franklin Salcedo

The organization has never had a dedicated practice space. For nearly 10 years, they would move from baseball diamonds in public parks to the gym at Elmwood Community Center once the weather turned cold. But, in 2019, inspectors found asbestos, mold, a leaky roof, and a broken boiler. The city decided the repairs needed for the center to be safe were too costly. So, they closed it.

“I feel bad because we need more support from the city, from the state. But between you and I, I don’t know but I believe that the high class people don’t like that our kids get a degree and go to college. I don’t know why they don’t want to invest, you know, in better sport insulation to try to take our kids from the street. Because I believe that if we have people that really really pay attention to the youth, maybe we don’t have a lot of crime on the street. You know, a lot of kids on the jail….But we need to continue to try.”

—KENNEDY ARIAS

CONTINUE THE TRADITION

Antonio grew up in a baseball family in the baseball capital of the Dominican Republic, San Pedro de Marcoris. His older brother, Rufino Linares, played in the MLB. Antonio played in the minor leagues for a few seasons before returning home and becoming a coach. He tells me about all of the baseball players, or peloteros, he coached back in the Dominican Republic that went pro in the US.

“Alfonso Soriano pasó por nuestra liga también. Yamaico Navarro, Joel Guzmán, Alexi Ogando, Miguel Mejía con los Cardenales de San Luis.”

—ANTONIO LINARES

Antonio returns to the line of kids, aged 9-12. Some of them are dwarfed by their gloves that are just a little too big for them. But all are ready to catch the ball, to continue the tradition that their fathers and grandfathers brought with them to this country, to become peloteros.

Antonio hitting grounders to the peloteros-in-training | Photo: Ana González