Episode

Highlights

NOT YOUR AVERAGE GRANDPA

Ralph holds his 1978 Grammy | Photo: Cheryl Adams

On the surface, Ralph seems like any other grandfather. Only, unlike your grandfather, his memorabilia includes a Grammy, photos with Muhammed Ali, and gold records. There are boxes of posters and framed, chart-topping records like “Don’t Take Away The Music”, “Check it Out” and “Heaven Must Be Missing an Angel”.

Ralph stands in the stairwell surrounded by the memorabilia from his old life | Photo: Cheryl Adams

An old photo of Vicky Vierra singing | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Feliciano “Flash” Tavares | Photo: Cheryl Adams

BORN INTO MUSIC

“Now, my father was a musician. He played in a band called the Creole Sextet was the name of the band, and my Aunt Vicky sang.”

—RALPH TAVARES

At the Fox Point Boys Club (left to right): Feliciano (Butch), Perry Lee (Tiny), Victor, Antone (Chubby), Arthur (Pooch) and Ralph Tavares | Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Tavares

“Here’s what happened: one day, we were at one of the Cape Verdean picnics they used to have back in those days… And during one of the intermissions, there was a young kid that came up on stage, and he came up and he sang a song by Frankie Lymon. And all the girls in the crowd went crazy. And we looked at each other. And we said that’s what we want to do.”

—RALPH TAVARES

CAPE VERDEAN FIRST

Ralph knows he’s dark-skinned, but when he’s younger, he doesn’t realize this makes him another race from his white neighbors, especially the Portuguese ones whose culture is so similar to his. He and the rest of the Tavares siblings think of themselves as Cape Verdean first, and then Black.

The six youngest Tavares siblings and one of their aunts | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“I never considered myself to be a Black American. I don’t want to be called that. That’s not what I am. You know, so I would always say I was Black with Cape Verdean descent.”

—TINY TAVARES

“Regardless of how much you identify with being Cape Verdean culturally… one is always going to be positioned, most likely, as being Black.”

—KHALIL SAUCIER, DIRECTOR OF THE AFRICANA STUDIES PROGRAM AT BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY

RACISM CREATES RACE

“We got arrested one night singing. What they did, they called us was disturbing the peace. They took us downtown. My father had to come and get us out of jail, and all we were doing was singing on the back porch. And this police officer came by and said that he got a complaint that we were disturbing the peace.”

—RALPH TAVARES

“The Cape Verdean from Pawtucket understands that he or she is Black when the hands are on the hood of the police car. It doesn’t matter if they think they’re black prior to or Cape Verdean. They’re Black when the violence of racism is being enacted. That’s when race is created.”

—KHALIL SAUCIER, DIRECTOR OF THE AFRICANA STUDIES PROGRAM AT BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY

Ralph enlisted in 1962 | Photo: Cheryl Adams

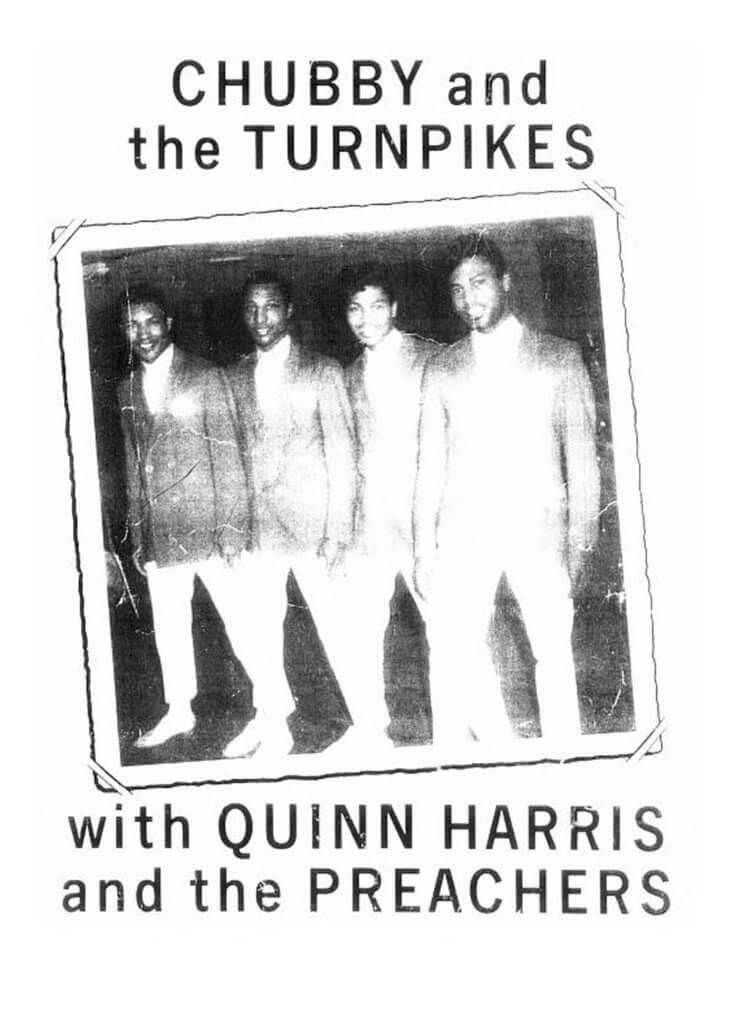

Chubby and the Turnpikes played all the local venues | Photo courtesy Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame

CHUBBY AND THE TURNPIKES

The Tavareses are paying their dues, honing their act, and making some money in the local venues, but nothing pans out for years. The younger brothers are still playing clubs in New England when Ralphs returns from the Army in 1965.

“When I came home, I couldn’t find any work. And then I saw my brothers singing. They were at the Blue Flame. And I was sitting there and I was and I had seen some of the groups that came through from Detroit. And I said, we were just as good as they were….That’s what made me not reenlist and form the group.”

—RALPH TAVARES

Being Black in America and performing that Blackness to crowds in the late 60s/early 70s is not easy. Off stage, the brothers face the same sort of issues they experienced with white folks their whole lives.

Rick James

“I remember – who was it that came up to us – Rick James… And he hadn’t become famous yet. But he came to see us performing in the club that we were playing at. And he almost started a riot because they thought we were invading their territory.…

We were black Americans, that’s all we considered ourselves, you know. But being Cape Verdean, we didn’t think there was a difference, we just thought there was just Black and white. I didn’t know that there was a discrimination between the races as far as ethnicity, you know, where you were born, where your families are from. As a matter of fact, we used to tell them, ‘We’re closer to Africa than anybody over here in this group!’“

—RALPH TAVARES

Chubby and the Turnpikes change their name to Tavares to appeal to a more international audience | Photo courtesy Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame

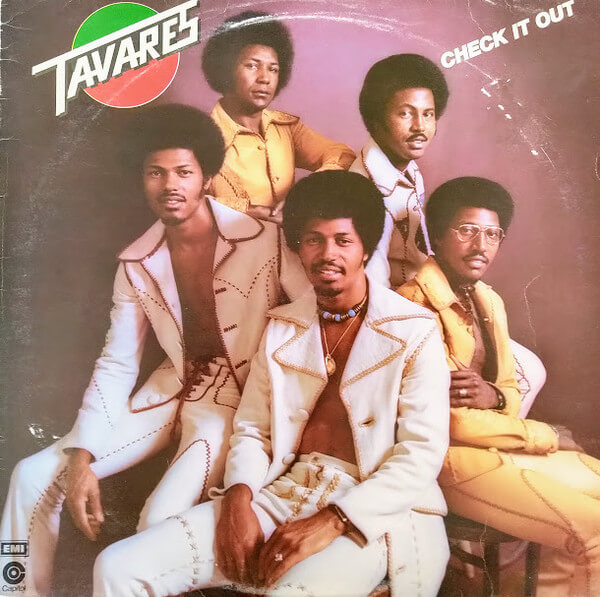

CHECK IT OUT

In 1973, Capitol Records gives them a shot: Tavares can record one single as a test. However the single does on the charts will determine whether or not Tavares gets that coveted multi-record recording contract.

With a little help from an appearance on Soul Train, ”Check It Out” makes it to number 20 on the R&B charts. Tavares lands the deal.

Tavares’s first single

“Oh, it was unbelievable. Anything that was happening to us then felt like a dream. Because we had been waiting for so long. We have been singing all the different local clubs…But nothing was materializing. So, you know, we were making a living as far as taking care of ourselves, but not being able to take care of our families or anything. And then when we finally started making records, it opened up for us, you know.“

—RALPH TAVARES

“Check it Out” is the first hit of many for Tavares. They put out their first full-length record through Capitol records in 1974. Their second, Hard Core Poetry, comes out later that year and charts even higher. Their touring schedule becomes more international and instead of clubs, they’re playing stadiums. The Tavares brothers are becoming stars.

HONORARY WHITES

In 1979, Reverend Jesse Jackson organizes a tour of American pop groups in South Africa. He invites Tavares. And the trip makes it clear how the world sees the band.

“Maybe the third week we were there that we found out and our passport says that’s when they gave us our passports back, that we were there as ‘honorary whites’. Can you imagine? That’s the only way they would let us into the country on our passport was stamped ‘honorary whites.’ Who knows what that means? Because we were still dark, you know? What does that mean?“

—RALPH TAVARES

"WE SHOULDN'T BE BACK AT THAT PLATEAU AGAIN"

2020 has also brought a season of civil rights protests and uprisings unlike anything our nation has seen since the movements in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It’s forcing the Tavares brothers to return to conversations they thought were over and done with.

“We worked in the South when we were younger, and we went through, ‘You couldn’t, you know, sit in this restaurant. You couldn’t sit at that table, you had to sit at this table. You couldn’t come into the front end, you had come to the back, we went through all of that… It shouldn’t be there. We shouldn’t be back at that plateau again, but here we are.’

—TINY TAVARES

DON'T TAKE AWAY THE MUSIC

“Fortunately, for us music did give us a better way and more respect to extent that people who may be prejudice weren’t as prejudiced because of what we did for a living. So, that kind of kind of gets you through some of the rough spots. But when I think to the people who didn’t have that privilege, that advantage. Imagine what they went through, you know. And it’s proven. Look at all the people who’ve died to get us where we are today.“

—TINY TAVARES

It all makes me think of another famous Ralph, Ralph Ellison, who wrote: “Perhaps in the swift change of American society in which the meanings of one’s origin are so quickly lost, one of the chief values of living with music lies in its power to give us an orientation in time. In doing so, it gives significance to all those indefinable aspects of experience which nevertheless help to make us what we are.”

The Tavares brothers are still close today | Photo courtesy Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame