Episode

Highlights

EXCLUSIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES

“If you were Chinese-American, you weren’t necessarily welcomed. People of my generation, I think in many cases, even though they had college educations, ended up in the restaurant business. And I think in part, this is an expression of employment exclusion in that generation.”

—JOHN ENG-WONG

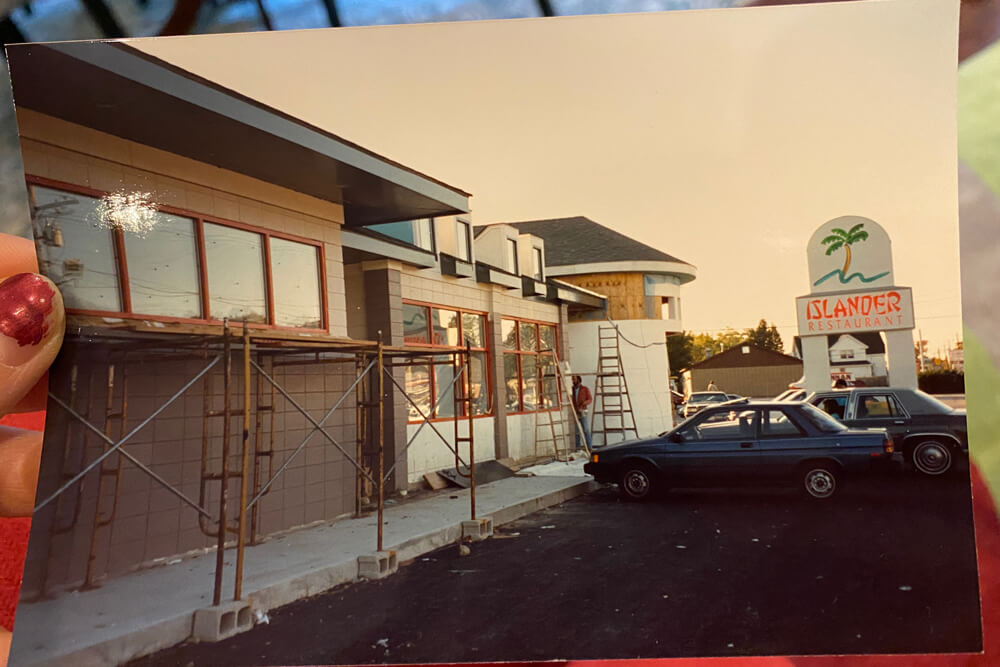

Chenelle’s family has owned restaurants since before she was born. In the 1970s, her grandfather and great uncle opened up the Islander restaurant in Warwick and ran it until they retired in 2000. In 1982, her father, Charlie Chin, opened up the first location of Asia Grille in Lincoln, a predominantly white suburb just north of Providence.

Chenelle holds a photo of The Islander restaurant under construction

Photos: Courtesy Chin family

Two members of the Chin family on the roof at The Islander in Warwick

A PATH OF HER OWN

“When I was in middle school and high school helping out, I didn’t think too much of it. I used to just work on the weekends, and holidays and vacations. And it wasn’t until I got to college that I started thinking about, is this something I’m going to do long term? What am I going to study in school and major in? And should it be something that’s kind of related to the business eventually or my own path?”

—CHENNELE CHIN

On holidays and summer breaks, Chenelle would return to Asia Grille and feel conflicted. Her parents built this restaurant to provide for the family. If Chenelle were to leave and pursue her own career, would that be selfish? Would her parents feel abandoned?

Chenelle and Charlie Chin in front of the new Asia Grille | Photo:Ana González

Laundries, restaurants and watches

All of the opportunities and choice available to Chenelle can be traced to a single family business: a Chinese laundry in New York City in the 1930s, where Len Bold Chin, Chenelle’s grandfather, finds work as a newly-arrived immigrant.

Laundryman Wo Sing Chin in Providence | Photo Courtesy John Eng-Wong

A Mee Hong table setting from the 1930s. Len Bold Chin would eat at Mee Hong after working at Thomas B. Gray Jewelers. It’s there that he finds community and place to stay. | Photo: Providence Journal Archives 2014

PROVIDENCE'S forgotten CHINATOWN

A lot of people don’t realize that Providence had a Chinatown. And it was demolished by the city.

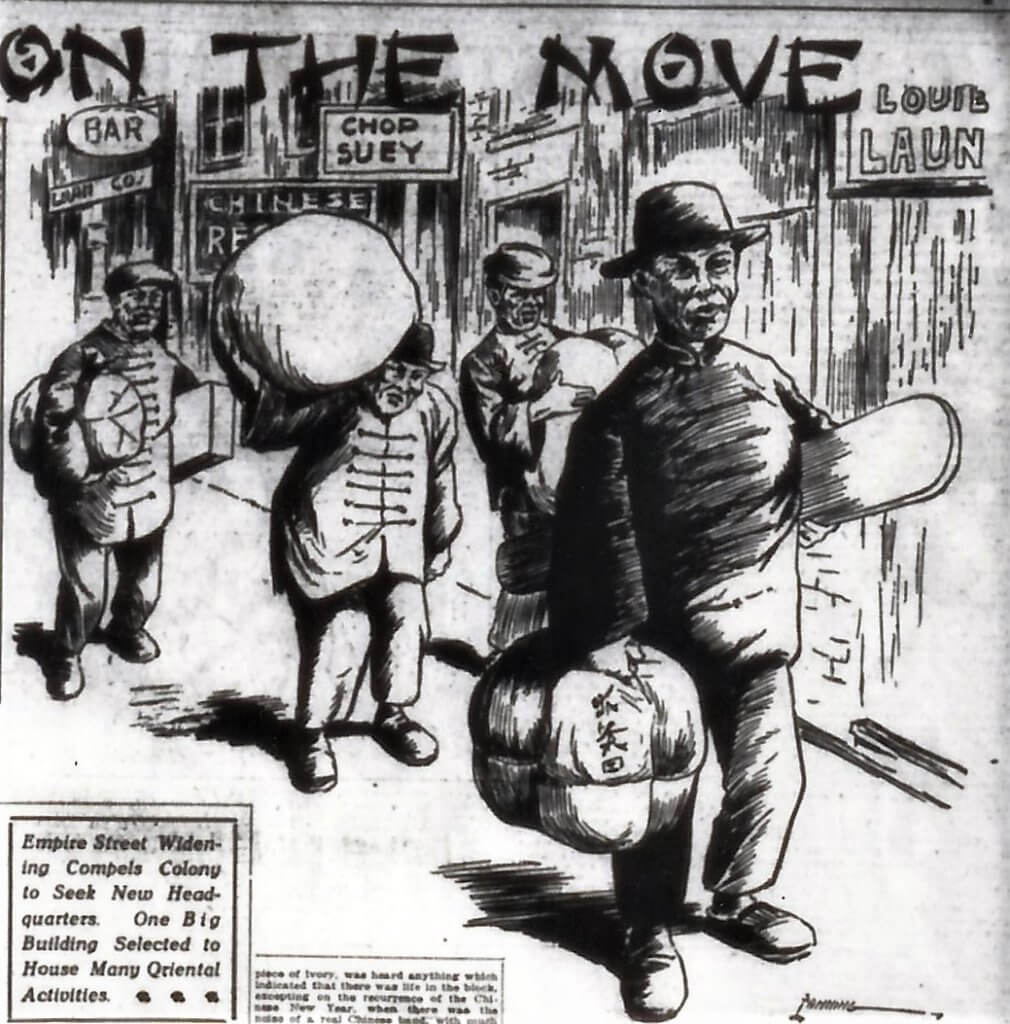

“Originally, it was along Empire Street. Empire Street was changed very drastically in 1914, when the street was widened. Up until that point, it only been a, you know, a hop skip and a jump wide. And I think in part, actually, to clear out the tenements that were along Empire street, and maybe, and to cleanse it of the Chinese, I don’t know, the city fathers decided to widen the street and to lengthen it. At that point, the Chinese collected themselves. And there was a big story in the Providence Journal with a hand drawing showing people with their belongings, hanging on a pole over their shoulder, marching off to the new Chinatown, which was on Summer Street.“

—JOHN ENG-WONG

Chinese Rhode Islanders depicted carrying their belongings from the soon-to-be-demolished Chinatown along Empire Street | Photo: Providence Journal Archives December 1915

Beneficent Church and basketball

Growing up, Charlie feels American. He listens to American music, he loves American comedians, like Redd Foxx. And he loves sports. Charlie says, as a kid, he’s never discriminated against for his race, but he does feel different from other kids.

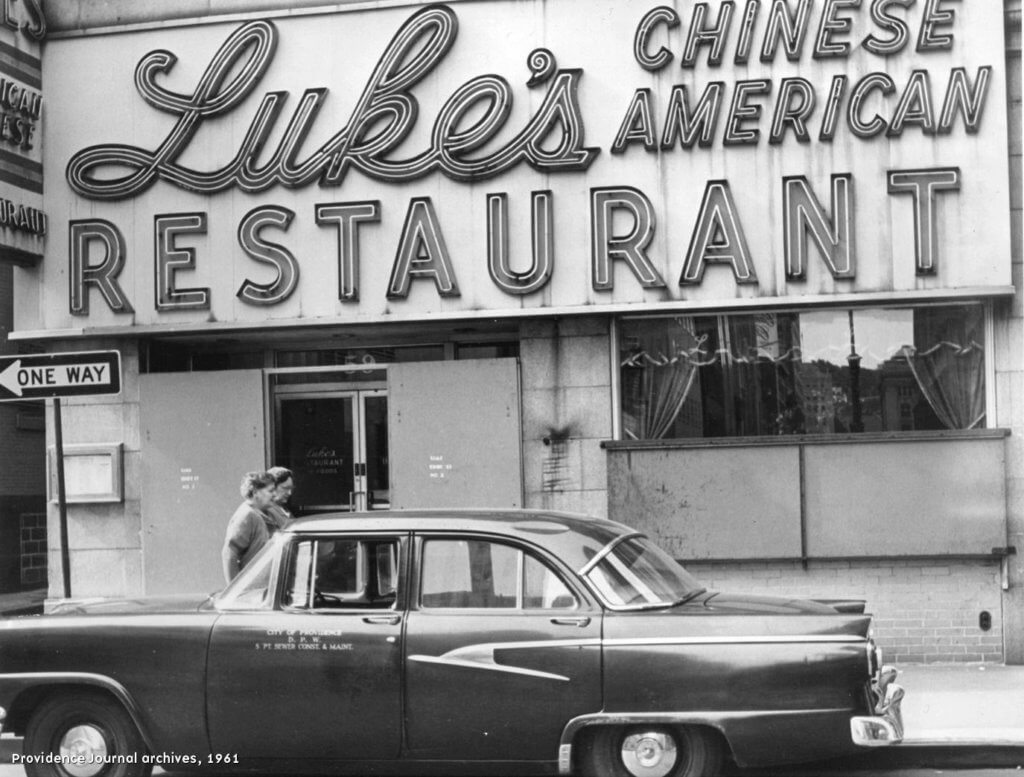

“After choir rehearsal at Beneficent, and we used to walk downtown and there’s five Chinese restaurants. We’d go in and say, do you need any help? You need any help? And so from one o’clock to about four o’clock, you know, you would do like peeling onions, potatoes, side work and all that. And you got paid only a couple bucks– two, three bucks– that was about it. But you were the richest kid in the neighborhood when you had that money in your pocket, you know?”

—CHARLIE CHIN

Luke’s Chinese-American restaurant in downtown Providence was one of the places Charlie would chop onions after school. | Photo: Providence Journal Archives 1961

VINCENT CHIN AND BEING A HYPHENATED AMERIcan

“The thing that really kind of like, you know, seared in our mind was the Vincent Chin incident.”

—CHARLIE CHIN

Vincent Chin is a 27-year-old Chinese-American kid whose life is nearly identical to Charlie’s.

“They caught him in the McDonald’s, and they beat him and killed him….

So you see examples of that where if you’re not cautious and you think, ‘Hey, I’m an American, too.’ Yeah. You’re a hyphenated American. Understand that. OK. And learn to live with it, and learn to deal with it and accept it.”

—CHARLIE CHIN

Being what he calls a “hyphenated American” excludes you from accessing all of the freedoms and liberty promised to citizens of this country.

TAKING UP MORE SPACE

Chenelle is born and grows up in Cranston. She makes it to Brown University and then gets her Master’s in Public Health at Johns Hopkins. Those experiences open up her world.

“I think it is important to stand up to injustice. If somebody is targeted simply because of their race, which we do see happening sometimes in our society today, and I don’t think that that’s right. And so I think I sometimes am trying to balance between doing what I feel is right and what I think my family would feel is right or would approve of.”

—CHENELLE CHIN

As a second- and third-generation immigrant, Chenelle knows she can take up more space in this country, but she’s still affected by her parents’ views and experiences. At times, she feels guilty for having more than them or even a different opinion. But mostly she’s grateful.

Chenelle and Charlie Chin before the opening of Asia Grille in Garden City | Photo: Ana González

A GREAT SOCIETY

While Charlie felt like his success was limited to the restaurant business, Chenelle has other options. Still, she has decided to commit her time and skills to the family business. And both Charlie and Chenelle are enjoying this new dimension of their father-daughter relationship.

“The value in a society, the value of any society is not in its monuments or riches or anything like that. It’s in how you treat your older generation before you and your younger generation. That’s what determines a great society.”

—CHARLIE CHIN