Episode

Highlights

AMASA SPRAGUE AND NICHOLAS GORDON

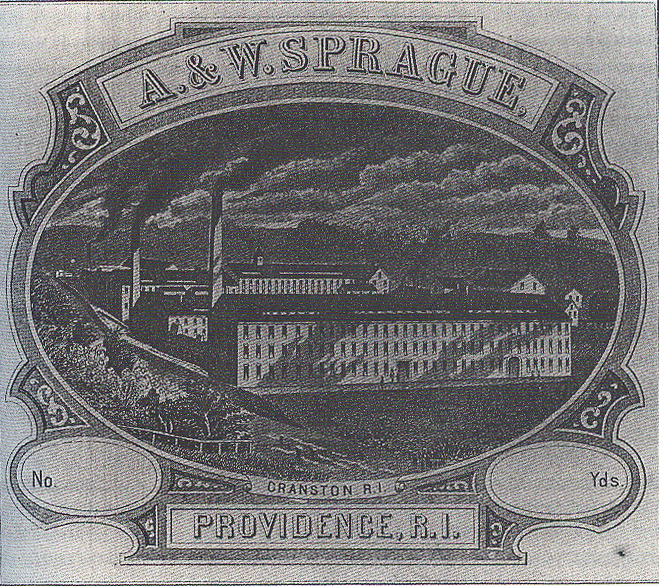

At its height, the Sprague mill employs over 500 workers, most of them Irish immigrants who flood into the port of Providence in the mid-1800s to escape British colonization back home and find work, in their minds, in the land of endless opportunity.

The Sprague Mill today | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“The Irishmans were considered dogs. They weren’t even considered white.”

—PAUL CARANCI

John Gordon’s oldest brother, Nicholas, comes to Cranston in 1836 to try and find a better life for his mother, sister, and three younger brothers back in Ireland.

Nicholas Gordon opens his store within the Sprague mill village in Cranston, but outside of the script system. He starts selling his goods at lower costs than the mill stores. And, he realizes he can make even more money if he starts selling alcohol.

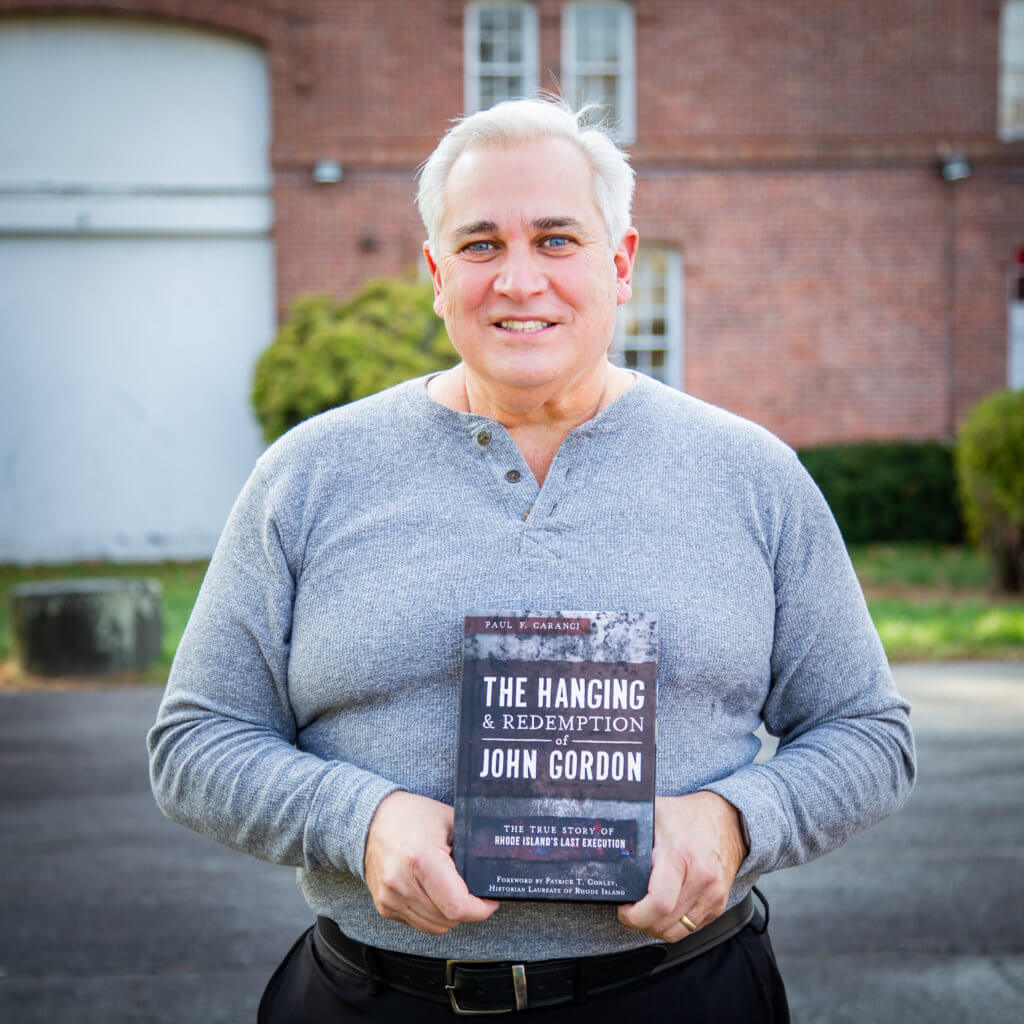

Paul Caranci and his book on the Sprague property, which is now the Cranston Historical Society | Photo: Cheryl Adams

ARE THE IRISH WHITE?

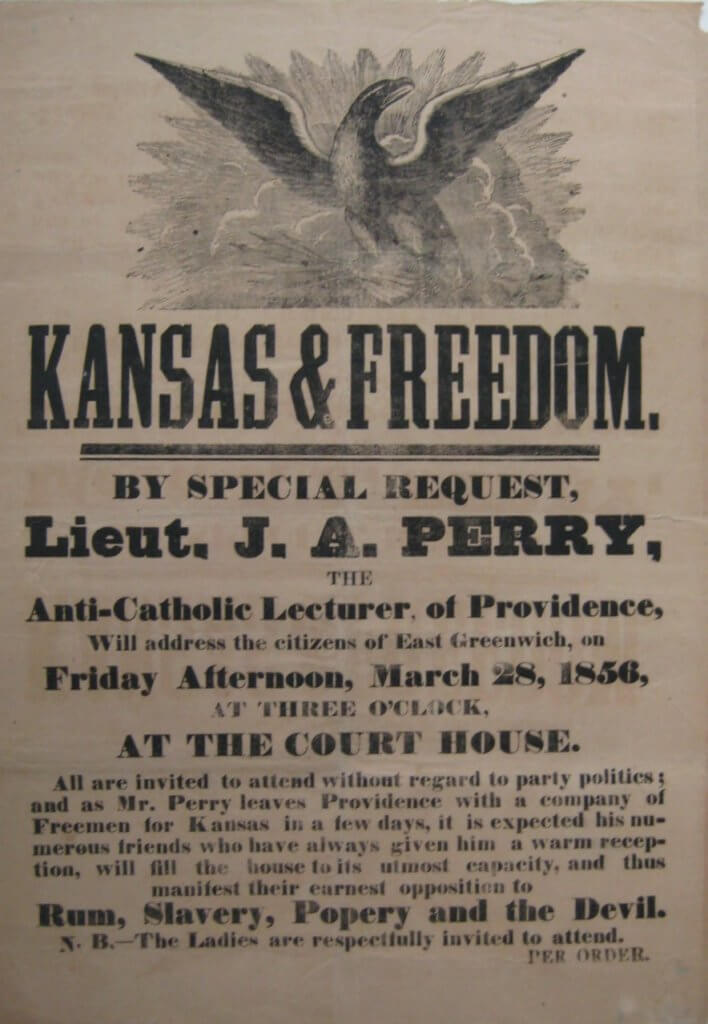

“There was intense fears of Catholics. You know, we live in a world today where that’s not common. …But when you link the fear of immigrants, particularly the Irish in Rhode Island, and coupled that with this profound fear of Catholicism, and kind of deep-seated hatred, it became a very powerful political force in the state.”

—ERIK CHAPUT

The ruling Protestant elite feared Catholicism would lead to the Pope controlling the state. | Photo: Courtesy of Russell DeSimone

Rhode Island in the 1800s is still ruled by descendants of the original English families who colonized the land in the 1600s. Not only that, they’re still using the Colonial Charter granted to them by the King of England in 1663 as the state constitution.

“It made it very difficult for workers to take a position – who could vote – to take a position that was going to run counter to the mill owner. The Sprague complex in Cranston is a perfect example of that they own the land, they own houses that you were renting. It was a complex. It was hard for laborers to break free of the grasp of a mill owner.”

—ERIK CHAPUT

The Sprague textile mill in its glory | Photo: Courtesy of New England Historical Society

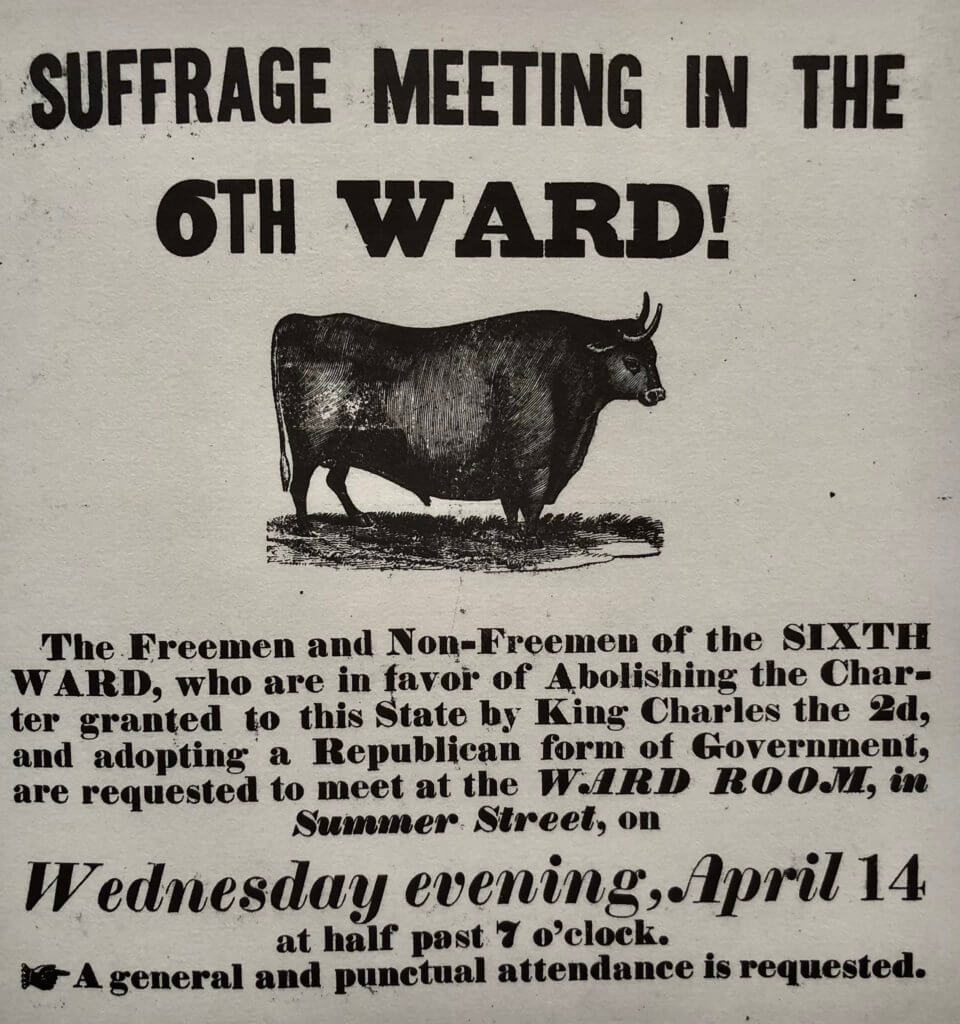

In 1842, just one year before the Gordons would arrive in Cranston, this tension between the disenfranchised working classes and the comfortable ruling class boils over in a series of events that historians call “the Dorr Rebellion”.

“What also is happening concurrently with that debate that’s going on is this question: Are the Irish white? Are they going to be of the same status? Is their skin color going to allow them to be at the same status of Protestants? And in Rhode Island, the answer was very clearly ‘No.’”

—ERIK CHAPUT

The Dorr Rebellion was like a mini revolution. This broadside advertised a meeting to rewrite the state constitution and expand voting rights | Photo: Courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society

A REJECTION AND A REUNION

“The town council…voted not to renew [Nicholas Gordon’s] liquor license, because they blamed him for Irish workers in the mill coming in drunk and late and increase in accidents and lack of productivity and all the things that went along with being, you know, drinking. And Amasa Sprague made it public that he was going to take away his liquor license.”

—PAUL CARANCI

Paul Caranci | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Nicholas is still able to pay for the passages of his mother, Ellen, his sister Margaret, and his brothers, Robert, William and John Gordon from Ireland. In July of 1843, the Gordon family is reunited for the first time in nearly a decade.

A MURDER MOST CRUEL AND ATROCIOUS

The night of the 31st, Amasa Sprague’s wife, Fanny, says he left their mansion to check on the livestock before nightfall. The normal route would take him past the mill, through the woods, and over a footbridge to cross the Pocasset River into Johnston. Right as he reaches the other side of the river, he’s shot in the wrist. Injured and bleeding, he attempts to run. The assailant’s gun jams, so he knocks Sprague to the ground. The attacker bludgeons Amasa with the butt of the gun until the gun shatters and the almighty mill owner crumples into the snow.

The Pocasset River today where Amasa Sprague was murdered almost 200 years ago | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“They saw an opportunity not only to make an arrest in a high profile murder. Murder case of the century – this was like the OJ Simpson case of that day–…but then they could create a situation where the could fuel more bigotry against the Irish, if you blame it on an Irishman. So, they found their perfect guy in John Gordon.”

—PAUL CARANCI

The State is desperate to make a conviction. After they arrest Nicholas and John, officials also arrest William in connection with the murder. Every member of the Gordon family is questioned. Officials even bring in the family dog to take paw prints. John and William are scheduled to be tried together in Rhode Island Supreme Court on April 8, 1844 for murder.

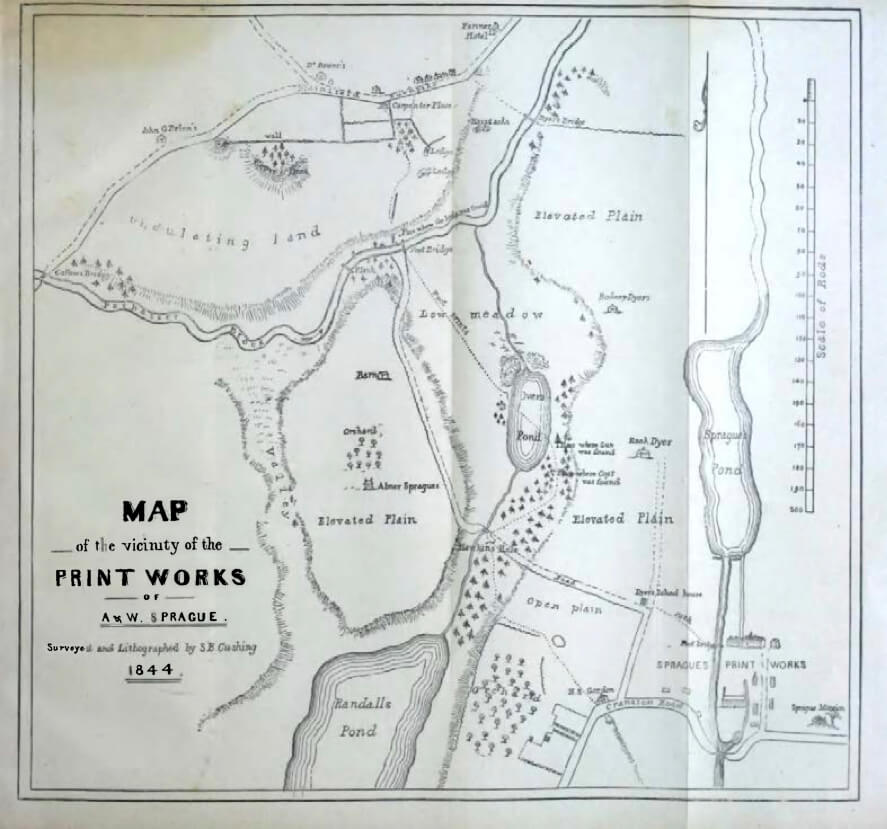

A map of the Sprague property in 1844 | Photo courtesy of the Rhode Island State Law Library

THE TRIAL OF JOHN AND WILLIAM GORDON

“12 jurors on each one. Everyone was a Yankee. There wasn’t one Irish Catholic among any of them.”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

Presiding over the trials and their Yankee jurors is another tried and true Yankee. An anti-Dorr, anti-immigrant Whig. Chief Justice Job Durfee.

“Chief Justice Job Durfee, who’s the head of the Rhode Island Supreme Court will say to the jury, which is unbelievable, that ‘if you find yourself listening to a native-born witness versus an Irish Catholic immigrant witness, you should give greater credence to the native-born individual, rather than the newcomer.’ Today, my God, a defense lawyer would jump up in the air screaming ‘Hooray!’ because he just won the case with that kind of discrimination.”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

Scott Molloy | Photo courtesy of University of Rhode Island

All together, there are 102 witnesses in the 9-day trial. Only a handful are Irish and actually know the Gordons personally. One witness actually mixes William and John up on the stand.

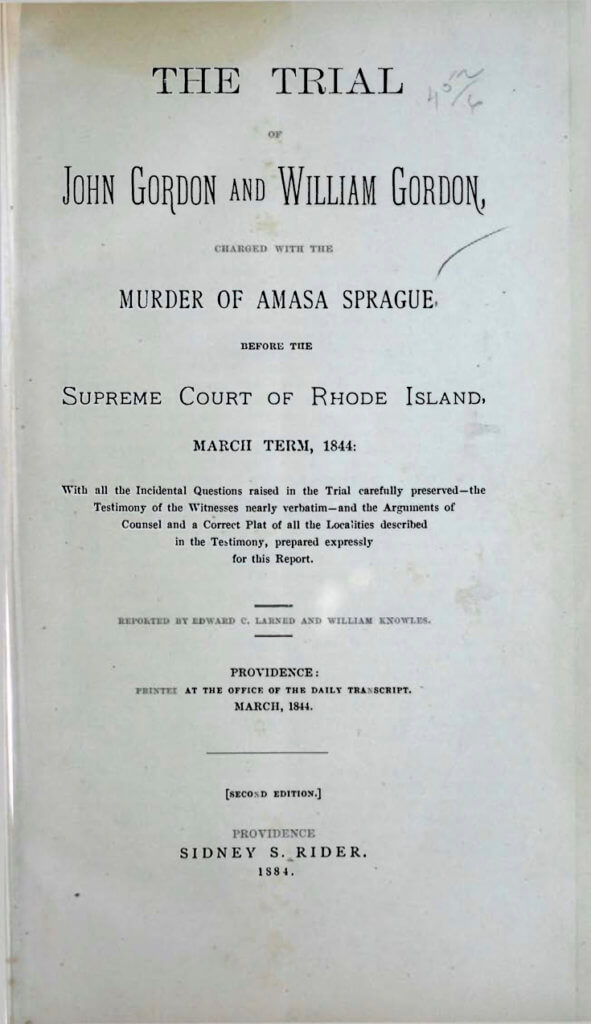

Two reporters wrote a transcript of the trial in 1844. The full transcript is available in the episode resources below | Photo courtesy of Rhode Island State Law Library

“They never had a witness who could say, ‘Yes, I saw John Gordon do it.’ That wasn’t there. There was circumstantial evidence that, you know, I wouldn’t want against me, but who knows? You know, it’s just, it just wasn’t fair. That’s all.”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

A Yankee witness gave William an alibi, and it frees him. But not John. The youngest Gordon brother is sentenced to death by hanging.

VALENTINE’S DAY, 1845

On Valentine’s Day, 1845, hundreds of Irish immigrants from New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut gather in Providence dressed in mourning. They surround the gallows, where, inside, a private crowd of politicians is gathering to watch John Gordon hang. He’s not even 30 years old.

An Irish Catholic priest, Father John Brady, also comes to John Gordon to hear his last confession.

“And then Father Brady does a fascinating thing. He in a sense, scolds the powers that be there. And he says, ‘John, forgive your enemies. They don’t know what they’re doing.’ He said, ‘because you’re going to join a myriad of other Irish martyrs who have been killed for the same thing: Nothing.’”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

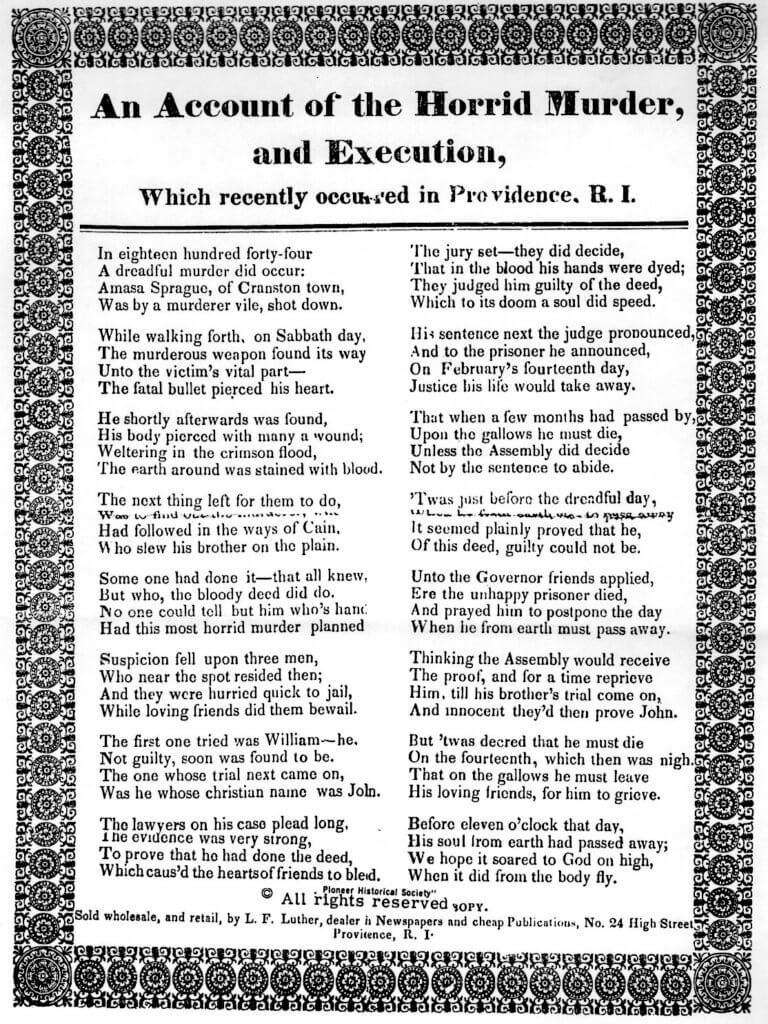

A ballad recounting the whole story of Amasa Sprague’s murder and John Gordon’s execution

A COMMUNITY CHANGED

“Because of… the bigotry, prejudice, a whole group, a whole culture lost something. You know, to them, America was no longer viewed as a land of opportunity. And the court system was no longer viewed as a place we go to administer justice. And the government itself wasn’t trusted by anybody of Irish descent or Catholic faith at that time, because of this.“

—PAUL CARANCI

The public backlash against John’s execution has one bittersweet consequence: it stirs up anti-death penalty activism. And seven years after John Gordon’s execution, Rhode Island abolishes the death penalty entirely. It’s the first state in the country to do this. John Gordon’s execution is Rhode Island’s last.

The Sprague property today is home to two Catholic churches, St. Anne’s and St. Mary’s. The spot where Amasa Sprague was murdered as well as the Gordon family’s home have been replaced by a huge Catholic cemetery. | Photos: Cheryl Adams