Episode

Highlights

CAN'T STAND THE COLD

“Tienes que estar encerrado desde la oscuridad, del frío. No soporto el frío, todavía. Hoy 26 años. I can’t. I can’t.”

Translation: You have to stay inside because it’s so dark and cold. I still can’t stand the cold. I’ve been here 26 years.

—ZENAIDA

Like so many other Puerto Ricans, and really most immigrants living in the cold of New England instead of their warmer homelands, winter makes Zenaida long for the land of her childhood.

“I miss my country, my family. I miss my people, the sun. I love the sun. I’m a beach girl. I used to go to the beach every weekend. My family is from the campo. So, I go in the river y climbing the tree pa’ coger mango y corriendo las gallinas. So, I get goosebumps.”

—ZENAIDA

Los García in Puerto Rico in the 1980s | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

Zenaida’s aunt in front of her grandparents’ home in Maunabo | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

A WILD GIRL

Zenaida loves going to the beach, which is really easy to do on a tropical island. She goes as often as she can after school and on weekends. One day she’s there with her sister, and one of her sister’s friends introduces her to a boy who would change her life.

“So ese dia él trajo al primo, mi ex, y me lo presentó, so there we start to talk and talk hasta que we hook up. Y siempre nos encontrábamos en la playa.”

Translation: So, that day, he brought his cousin, my ex, and introduced him to me….And we would always find ourselves at the beach.

—ZENAIDA

Zenaida (right) at age 13 | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

“I was a wild girl. So I think I still…Creo que porque siempre crecí en la casa, trancada. Cuando salí afuera I was like a little bird. Que los soltaron de la jaula y hacía travesuras, maldades con las muchachas. Siempre estamos haciendo cosas funny, alegre. O si vemos a un muchacho guapo por la calle, ‘¡Oye papi! ¡Que bueno tú estás!'”

Translation: I think because I was always raised in the house, locked up. When I left the house, I was like a little bird who jumped out of the cage to make mischief and do bad things with my girlfriends. We were always doing funny things. Or if we saw a handsome guy on the street, we’d yell ‘Oye, papi! Looking good!’

—ZENAIDA

leaving him, leaving puerto rico

“Él bebía. He used to drink with his boss and his cousin. And he came drunk at home to the house and start to fight with me. And that’s how everything started….”

—ZENAIDA

He starts to hit her. It happens the same way every time. He comes home drunk, wakes Zenaida up, starts arguing with her, things escalate. Zenaida would defend herself. Her husband would get angrier. She would call the police or a neighbor, and he would get scared and apologize, vow to never do it again.

“I put him on jail the last time he hit me.”

—ZENAIDA

Zenaida, pregnant with her first child, with her mother in Puerto Rico | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

“I was telling her ‘Mom, my marriage is like that. I’m going through this. So, I want to leave him.’ Ella me dijo, ‘Múdate pa’ acá. Vente pa’ acá conmigo.'”

—ZENAIDA

BREAKING FREE

Despite her fears, she does it. She breaks free of her abusive husband, boards a plane with her three kids, and lands intact in Providence in the summer of 1996. She’s able to live with her mother in an apartment rented from her cousin. She and her kids are alive but traumatized.

“They were crying every night asking for his dad. When his dad is coming. And that was breaking my heart. Si no hubiera sido por mis primos que vivían aquí y mi mamá y el soporte que tenía aquí, I don’t know how those kids, cómo iba a crecer.

Translation: If it hadn’t been for my cousin that lived here and my mom and the support that I had here, I don’t know how I could have raised those kids.“

—ZENAIDA

Zenaida’s three kids with their grandmother in Providence | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

mami

“I try to manage with “Have a nice day.” “Thank you for shopping at Walmart.” Because I don’t wanna get fired.”

—ZENAIDA

“And then I left after a year because my mother was sick.”

—ZENAIDA

Serafina, pictured here with her sister in Puerto Rico, died on a cold winter day in Providence | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

“Yo decía a mi mamá, ‘Mami, cuando tú te mueras dónde te entierro? Porque yo me quiero ir de aquí. Yo no quiero estar aquí toda mi vida.’ Mami murió y sigo aquí because my kids!”

Translation: I used to say to my mom, ‘Mami, when you die, where will I bury you? Because I want to leave here. I don’t want to stay here my whole life.’ Mami died, and I stayed here.

—ZENAIDA

It’s January 2009. A snowstorm is coating Providence when Zenaida’s mother passes away. Zenaida brings her mother’s body back to Puerto Rico to bury her.

getting help

One day, Zenaida’s at her doctor’s for her yearly check up. He asks how she’s doing, and she bursts into tears. He recommends she go get help at a mental health clinic called the Providence Center. That’s where she meets a therapist named Sandra. Sandra is a first-generation Mexican-American from Texas. She’s bilingual and is able to meet Zenaida where she’s at, both with her language and her mental health needs. Zenaida trusts her and begins to open up about her life.

“Como yo me pasaba llorando, durmiendo, no motivation, no self esteem. Y all my grief on my mother, from my sisters.”

Translation: How I was always crying, sleeping…

—ZENAIDA

Sandra helps Zenaida understand that she is suffering from depression and PTSD from the years of abuse and loss. Sandra guides Zenaida through the grieving process and gives her the support she needs to let some things go.

Zenaida and Ana walk through India Point Park | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“After I left Walmart and CVS, I tried to apply, and I was failing the application and the test when I applied for price rite, walgreens. Nobody want to hire me. So I was talking with Sandra. She told me ‘Zenaida, you want to find a good job, you need more vocabulary. You have to go back to class.’ And I wasn’t working. So I say, ‘Okay, I’m going back to class.’”

—ZENAIDA

DAVE'S CLASS

“My first impression was her coming into the room in sweatpants… And she was not carrying herself with the same poise and valuing herself in the same way that she, if you look at her now, she does.”

—DAVE

For Dave’s students, living in the US and speaking English was never something they planned to do.

“I went to Dave’s class….He was very nice…He want to hear us. Listen to us.. When I start to talk, I start to cry.”

—ZENAIDA

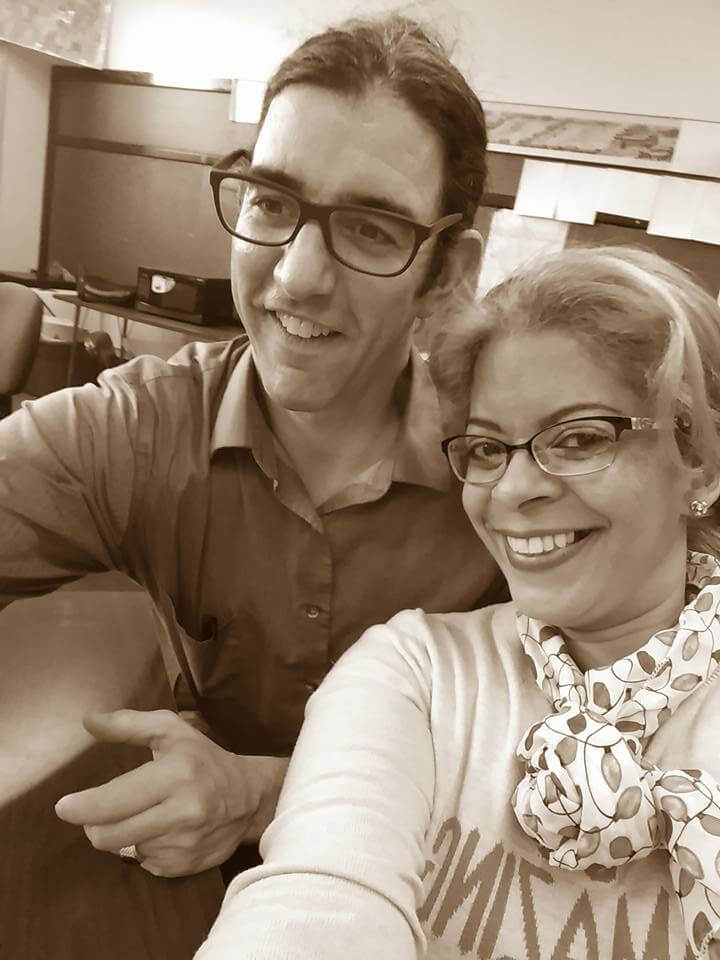

Zenaida and Dave at the Genesis Center circa 2017 | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García

the change agent

After months of writing, editing, and rewriting, Zenaida submits her story to the Change Agent.

“And I got the first place. So, I won the story in the Change Agent magazine.”

—ZENAIDA

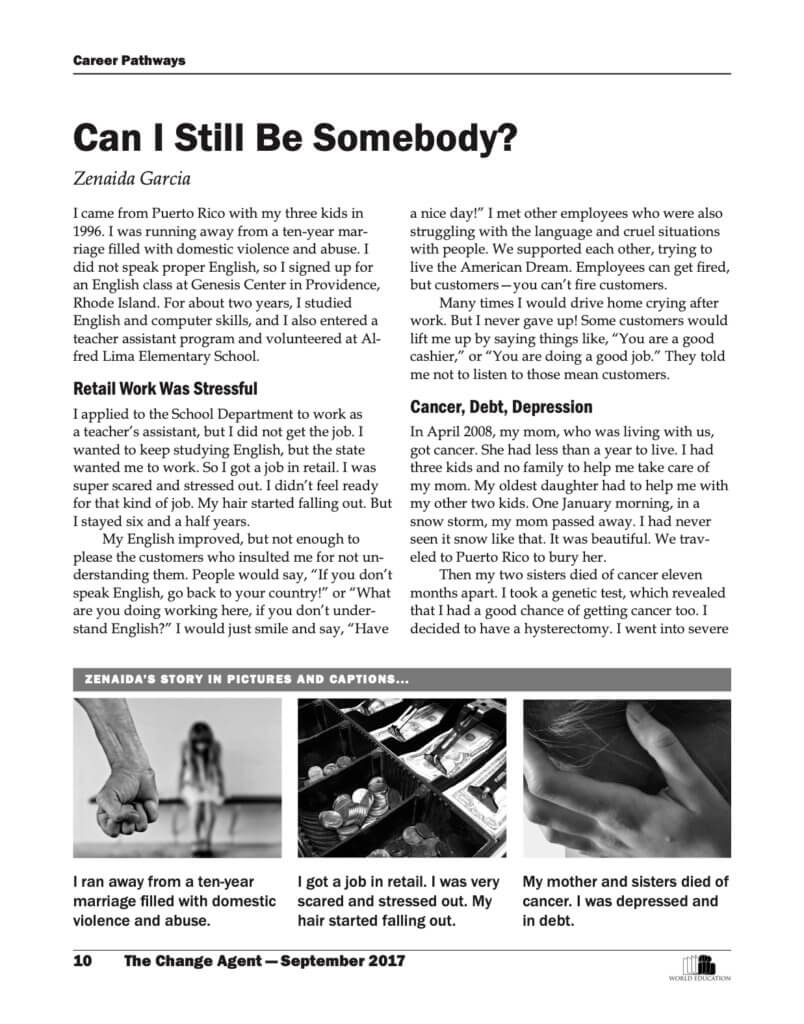

The first page of Zenaida’s essay. To read the whole thing, click here.

“In the process of taking stock of her life, she was able to gain some control over the confusion that she was stuck in. She was like, basically lost. And, you know, she was receiving benefits, she wasn’t working, she was, her self esteem was really down. And she didn’t really know what happened. Like she was blindsided by life.”

—DAVE

EMPOWERED WOMAN

The Change Agent invites her to give a speech at their national conference in Boston. Dave and Sandra go with her and record her speech, which she slays:

“Good evening. I started preparing to speak to you tonight. I look for inspiration on YouTube and found Oprah. In other words, I looked outside of myself. What I realize now is: an empowered woman can look inside of herself for inspiration. Look inside yourself. Tell your story, like I did. Sharing my story with you tonight has helped me to do that. Thank you so much.”

—ZENAIDA

una puertorriqueña americanizada

“I’m not the Puerto Rican that I was. I am another Puerto Rican now. I’m like americanized Puerto Rico –una puertorriqueña americanizada. And I don’t like that. I want to be the Puerto Rican 100%. Yo quiero ser la puertorriqueña que vive allá en la Isla.…. But, at the same time I don’t know if I want to go back. So I’m always fighting with myself.”

Translation: I want to be the Puerto Rican that lives there, on the Island….

—ZENAIDA

Much like the island itself, the nostalgia for a homeland where it’s never cold, where sapitos and coquis sing to you from the riverbanks never goes away. So, for now, Zenaida paints the walls of her apartment, cooks her own lechón, and lets the lights of her Christmas tree replace the warmth of a Puerto Rican sun.

Zeny and her Christmas tree | Photo: Courtesy Zenaida García