Episode

Highlights

FATE TURNS INTO FOLKLORE

“That case banged around Rhode Island interminably for decades and decades.’”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

A STRONG CATHOLIC

“John Gordon was a weak character. He drank too much, had difficulty holding a job. But the one thing he was, he was a very strong Catholic.”

—KEN DOOLEY

“And my thought was, if Gordon could only save himself by fully confessing the murder and putting himself at God’s mercy, so to speak. Is he gonna lie? I mean, God’s gonna know he’s lying, isn’t he? So my guess is that Gordon confessed, did not do the murder. And Father Brady was then emboldened to come out and throw it back in the faces of the Yankees. Circumstantial evidence. Can I prove it? Not in a million years. Can you prove it by religious practice or whatnot? You can come pretty close with it.”

—SCOTT MOLLOY

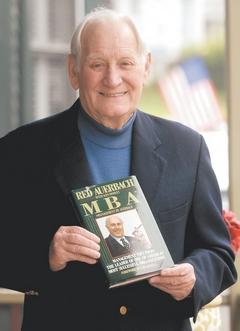

Ken Dooley wrote a book with Boston Celtics coach, Red Auerbach, before studying the Gordon case | Photo: Courtesy of Newport Daily News

THE PLAY

“And all of a sudden, I said, ‘Hey, there’s no question in my mind: John Gordon is innocent.’”

—KEN DOOLEY

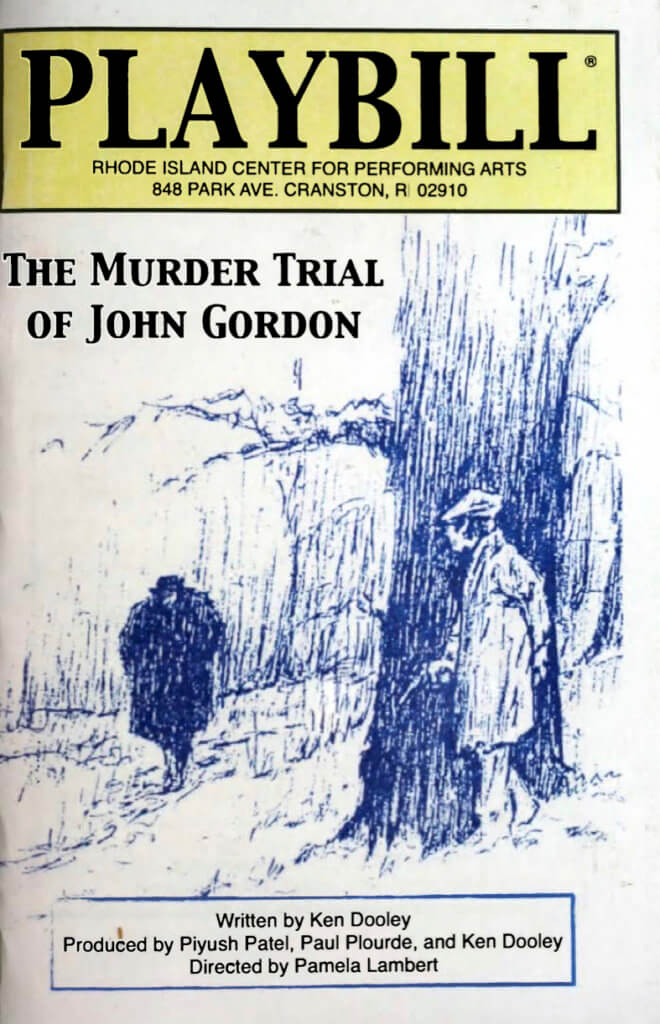

Ken starts doing what any writer would do: he begins writing the story of John Gordon. Soon, he has a script for a play. He titles it The Murder Trial of John Gordon. It premieres at the Park Theater in Cranston in January of 2011 to a packed house. Even in the 21st century, the story of John Gordon continues to draw a crowd

The playbill for Ken’s play in 2011 | Photo: Ken Dooley

A snapshot from The Murder Trial of John Gordon | Photo courtesy of Rhode Island Catholic

A PETITION FOR JOHN GORDON

“The play was on for a few days. And this man came up to me and said, ‘You really think that John Gordon is innocent, don’t you?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I definitely do.’ So, he said, ‘Well, what are you gonna do about it?’”

—KEN DOOLEY

A pardon for John Gordon, a man hanged in 1845, from the Governor of Rhode Island in 2011. At this point, it’s just an itch of an idea. But after three weeks of performances, the petition has 4,167 signatures.

Representative Martin is going to take John Gordon’s trial to the Rhode Island House of Representatives and ask for a new hearing for the last man executed in the state.

IRISH POLITICS

“Once the move got going, once Peter Martin and all had kind of spearheaded that, and, you know, given the composition of the legislature [LAUGHS]….I was pretty sure that it would have strong legislative support.”

—PAT CONLEY

Pat laughs about the composition of the legislature because modern-day Rhode Island politics is dominated by Irish-American politicians. 1906 marked the first Irish Catholic governor of the state, James H Higgins. In 1911, the first Irish Catholic Congressman, George O’Shaunessy, was elected to his first of four terms. And from the 1940s to today, Rhode Island has been a Blue state, ruled by a mix of Irish, Italian, and WASP-y legislative and executive branches.

It’s clear that the pardon of John Gordon is not only a way to clear an innocent man’s name, but it’s a flex of political power for Irish Americans. And it’s an example of how groups can use that power for good.

Governor James Higgings (left) and congressman George O’Shaunessy (right), some of Rhode Island’s first Irish Catholic politicians | Photos: Courtesy of Wikipedia

"GET YOUR PEOPLE LINED UP"

With deep support from the Irish political community, Peter Martin introduces House Resolution 5068 on January 11th, 2011. Peter wants to prove that the legal system can work without favors or cronyism. But that way is longer. January passes, then February, March, and April. He’s getting anxious, worried that House Resolution 5068 is going to be forgotten in the mix. But then, John O’Connor comes into his office.

“And John comes in and says, ‘Well, you know, that Gordon thing? We got a hearing coming up for you. Get your people lined up.’”

—PETER MARTIN

RESOLUTION 5068

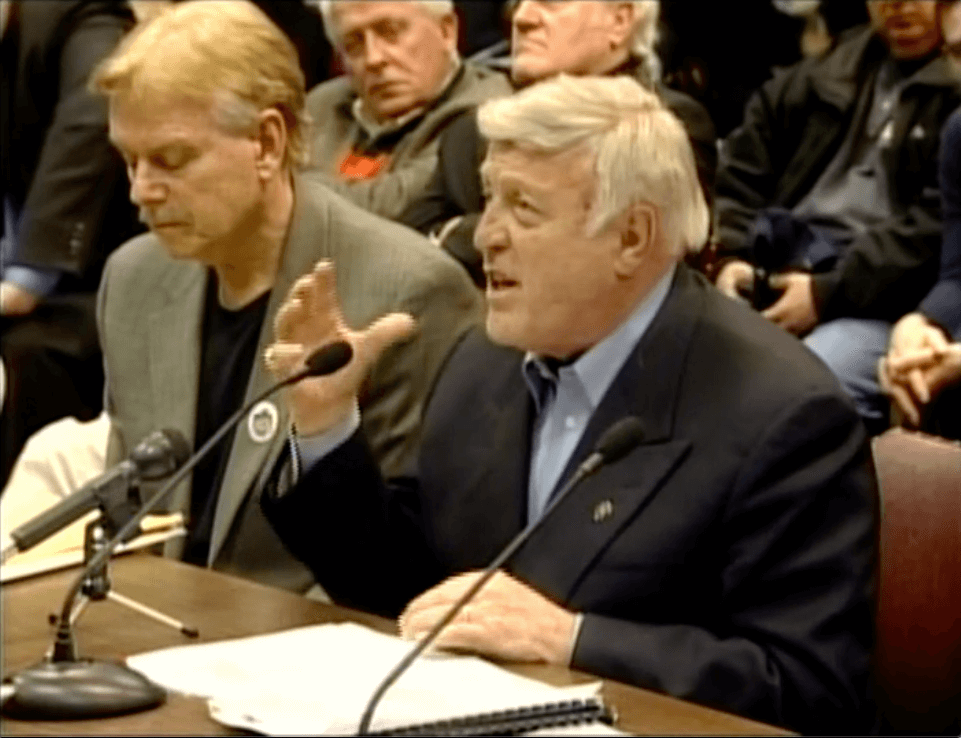

It’s May 4, 2011. The Rhode Island House Judiciary Committee is set to hear arguments for and against Resolution 5068. Pat Conley opens the arguments.

Pat Conley (right) testifies| Photo: Capitol TV

“My name is Patrick Conley. I’m here to testify in favor of the resolution…. What I want to talk about today briefly is what we will call the temper of the times, because that’s often undermined the temple of justice.”

—PAT CONLEY testifying before the House Judiciary Committee

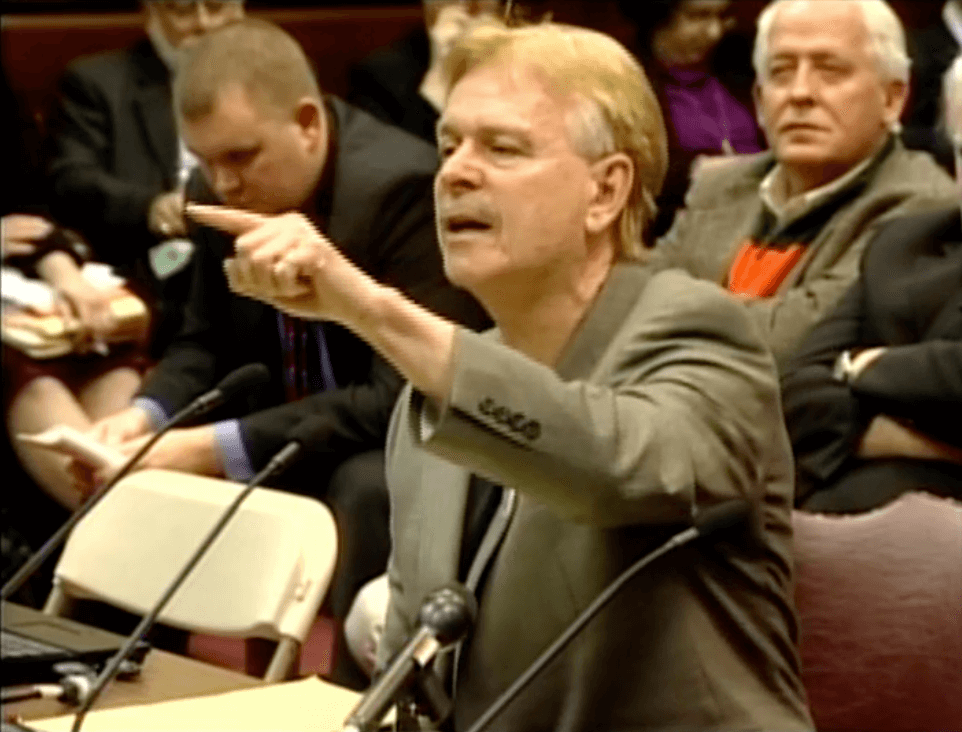

Scott Molloy describing the Gordon Trial | Photo: Capitol TV

“We will never be able to determine with exactitude whether John Gordon was guilty or innocent. What we can always be sure of, is that discrimination against Irish Catholics was the main reason for his conviction and subsequent execution. Thank you very much.”

—SCOTT MOLLOY testifying before the House Judiciary Committee

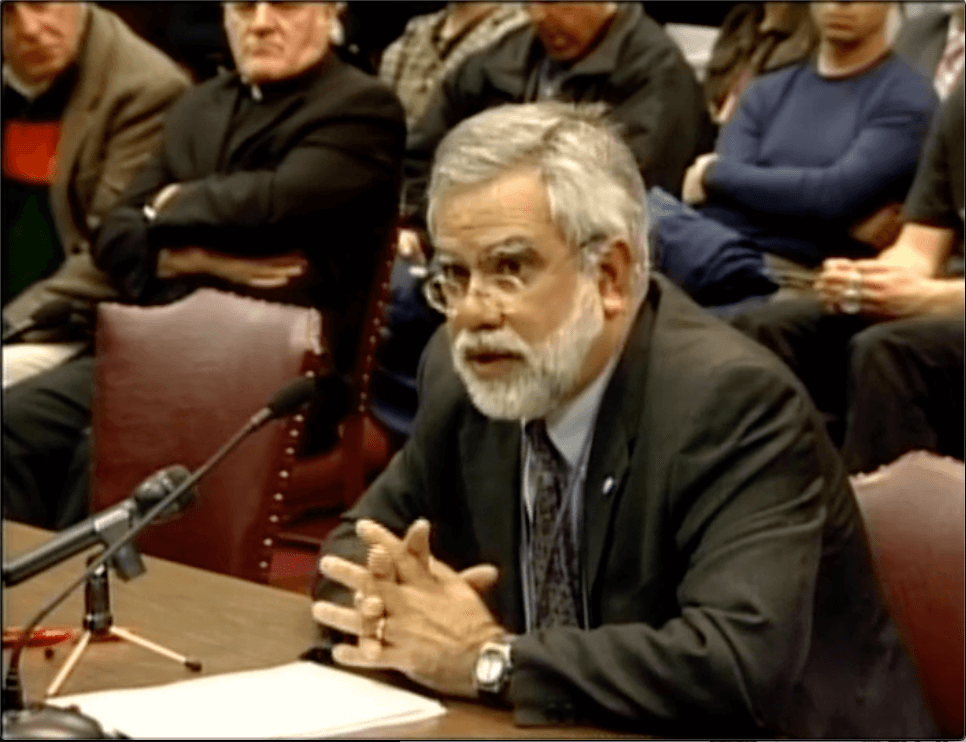

Assistant Public Defender Michael DiLauro goes over the details of the case | Photo: Capitol TV

“The Gordon case provides us with a teaching moment. We have a chance to look at…and see where we’ve been and where we’re going. And of course, if you were to act favorably on this resolution, we’d have the added benefit of righting what most people believe historically was a great injustice and a great wrong. And clearly that if you were to do that it would be an imperfect righting of a wrong but the best that we can do under the circumstances.”

—MICHAEL DILAURO testifying before the House Judiciary Committee

Bruce Reilly relates the Gordon case to the Brennan case, where two Irish-American brothers are currently serving life in prison for a murder they claim they did not commit | Photo: Capitol TV

“And if you’re sitting there in prison, doing life without parole or life, nobody cares about you. Nobody pays attention to your case. And our state does not have an Innocence Project. Our law school does not have an Innocence Project, and the few attorneys who have the time and space to, to to address these issues. I wish there were tons more. I wish the amount of energy that went into the Gordon case, went into the Brennon case, or someone else who’s sitting up at ACI. And I just like to say there’s people rotting away today, because of things like racism, mistakes, malice, oversight. There’s a lot of reasons why injustices occur.”

—BRUCE REILLY, Direct Action for Rights and Equality [DARE], testifying before the House Judiciary Committee

A PARDON FOR JOHN GORDON

The following Wednesday, May 11th, the House of representative votes on Resolution 5068. It passes unanimously.

“And I get a call from the governor’s office saying to me that the governor would like to have the pardon next Tuesday or whatever day it was. Short notice.”

—PETER MARTIN

Just like that, Governor Chafee agrees to right a wrong 166 years in the making. Peter tells everyone: Ken Dooley, Scott Molloy, Pat Conley, Michael DiLauro. They all prepare to witness the pardon of John Gordon on Wednesday June 29th, 2011.

“And we had the pardon, in the same room, in the same room at the Old State House on Benefit Street that John Gordon was found guilty. And that was powerful. That was really powerful.”

—PETER MARTIN

Governor Lincoln Chafee reads the pardon of John Gordon in the Old Statehouse on Benefit Street where John Gordon was found guilty 166 years before. | Photo courtesy of Johnston Sunrise

EILEEN, WE DID IT

“He’s no longer lying in a grave as a convicted murderer… They made up a medallion for John Gordon, and on the back it had the pardon. So my sister’s husband was in the Navy. He’s buried at the veterans cemetery, as is my sister. So after the pardon, I drove out there, and I dug a little hole, and I put it in, and I looked up, and I said, ‘Eileen, we did it.’”

—KEN DOOLEY

On the left, the medallion made for John Gordon’s pardon. On the right, Ken Dooley and Peter Martin at the dedication for John Gordon in October, 2011 | Photos: Peter Martin

THE ARC OF THE MORAL UNIVERSE

The story of John Gordon reminds the Irish-American community in Rhode Island that their start in this country is rooted in oppression.

John Gordon only lived in this country for 6 months before he was arrested. If he wasn’t executed, he would have died a small death, only to be remembered by a generation or two of his immediate family. His pardon doesn’t change anything about our criminal justice system today, but, for better or for worse, it’s a living example of that famous Martin Luther King, Jr. quote from his sermon at Temple Israel in Hollywood: the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.