Mosaic Community Essays

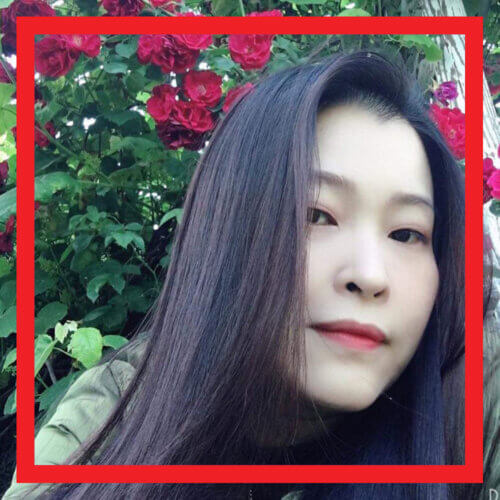

"A True Anchor Baby"

“Who is it?!” Mom stood silently, with her face turned towards me and her ear towards the door. BANG. BANG. BANG.

“Open the door ma’am, it’s the NYPD. We just want to ask you some questions.”

“Questions about what? I’m a single woman down here and I don’t open the door to nobody, I’m by myself down here!” Screamed my mom through the door, spitting in her Dominican accent.

The tiny hallway to our basement studio apartment muffled what felt like an echo, it was one of those days where the heat and humidity had left a coating on the cool white floor-tiles. I was petrified. Mom had not even opened the door with the chain on like she normally did when worried about who stood on the other side.

This was next level.“There was a shooting on your street ma’am, we just want to see if you heard or saw anything.”

BANG BANG BANG.

“I’ve seen nothing, heard nothing, and am not opening this door.” She stood quietly there, tense like a leopard with her ear perched, until we could hear the cops walking up the steps to the street-level and disappear.

There it was, the NYC I had heard of. A place where fault catches you like a cold and can land you in trouble you never touched. My mother did not have the right papers to answer the questions of any cop. “You cannot get into anything here” she would tell us. “Not until you’re old enough to have your own ID.” The consensus was that my mother could easily be deported, and that her two American daughters likely would not.

NYC was a place where a three-person family could live in a crowded apartment with no windows and still genuinely feel lucky. It was as if the ability to live in a mole-hole benefited our status in this country. Years later I will ask myself how we ever slept in that apartment, with the bedroom just a thin wall away from the building’s main boiler. It’s constant banging reminded me of the high-school mandatory reading of “The Jungle” and “Atlas Shrugged,” and I would dream of steamy canning factories and loud wrought iron foundries feeling as if I were manning the hammer myself. The city was always banging on something. I would count with the noise and dream of turning 18.

“You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.” Back when we lived in Europe I would sing these lines loudly with my sister, while rolling on the ambient-heated floor. We would listen to the Beatle’s karaoke album and try to visualize the rest of the world. Back then, we imagined the US, a place where we had been born. “We’re the kids in America, wooo.”

I grew up thinking about borders, cultures, the spaces between people. A Caribbean-Swede, an unlikely mix, an observant and careful child. I was a dark-skinned person but was, culturally and legally, a Swedish person. In my early teens I thought often of the difference between people, what magic commonality holds us together as a species, and what keeps us fighting, like scared animals caged, clinging to the arbitrary concept of nationality. “Young American, young American, she was a young American.”

No two immigrant stories are the same. And some people are immigrants twice. I have been the daughter of foreigners everywhere I’ve ever been. I have also always been a citizen of the places we’ve lived. Born to a Dominican woman and a Swedish man residing on a ship I am a literal anchor baby, politically and contextually, of the USA. My birthright is the epitome of privilege, and yet I got to observe firsthand, two times, the struggles and triumphs of immigrants in the latter two places through the eyes of my hispanic mother.

Growing up in Sweden I was surrounded by immigrants from every country that had had a recent conflict. Once you know that the nation takes the highest percentage of asylum seekers per capita in the world this fact may seem less surprising. My friend’s parents could never have imagined the place where they had ended up and instead dreamt instead of going back to where they came from. They all wanted to go home. Sometimes. When it would be safe again.

I grew up with second generation Iranians, Somalians, and Czechoslovakians. I found fellowship with kids who, like me, felt culturally removed from these places. We shared a prevailing stress about the future while also feeling like part of the nation’s perpetuating our parents’ statuses as “pending.” My mother gained Swedish citizenship because of my birthright but struggled for over a decade to have her positive outlook on life, her eleven years of study, and her work-horse approach to labor appreciated there; she was always too foreign, too dark, too loud, and too un-Swedish to thrive. She grew sadder and less hopeful for each declined job she qualified for. Interestingly she was forced to live off the Swedish welfare system, which supported her well enough to create fond memories in my reminiscences of the place.

Like every person from a developed country on this planet, my mother’s eyes began to point towards the US.

This was not a new destination.

She had sat under papaya trees and heard the stories as a child, remembered the nurses and the clean hospital beds from the windowless room where she had been in labor. Unlike many of the immigrants in our Swedish housing complex she did not long to go back to her native DR. Perhaps she dreamed of belonging to the great nation of mutts, cast-offs, and adventurers. Set out for a place that broadcasts loudly that you’re welcome if you work, and that whispers the opposite. Throughout my childhood she was obsessed with Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA.”

Just in-case someone needs to hear this: most immigrants take the plane. They overstay their “welcome” after-which they go into what can only be described as hiding until the solution presents itself. They get fake social security cards and pay into the social security system while working menial jobs for below minimum wage. They work for employers who know their status (how else could you pay below minimum wage and report otherwise?) and exploit their labor.

I knew at the age of 15 what Nina Roberts reported on Market Place in 2019; that this $13 billion surplus of never claimed, impossible to claim, Social Security benefit payments support the operation and sustainability of the American welfare system. I knew then that the Medicare taken out of my mother’s paycheck would never help her in a medical situation, and I certainly knew she would not, could not, burden our public services by calling for help had the need arisen. I also promised myself never to get hurt, call the cops, or even mention where she, or anybody else, worked, until I was old enough to have my own legal identity.

I learned early what it means to be an immigrant in a country that supports immigrants and asylum seekers. The experiences of people who arrive on foreign shores as the result of necessity and war.

I learned a bit later on what it means to be an immigrant in a country that villainizes and criminalizes the movement of people; the actions necessary to make this existence work, the sacrifices and contributions given at no benefit to them. No two immigrants are the same, but their wishes and dreams may be. Of citizenship, certainly, but importantly of protection and acknowledgement. Once my mother got her US citizenship, through my anchor-baby sponsorship, she gained access to all the opportunities afforded the people of the richest nation under god, but she keeps her history buried. I have the privilege of feeling safe enough to share a story she can not risk to tell.

My mind has wandered into the territories of immigrant experiences with an eye towards Haiti, Honduras, Syria, towards Afghanistan. Towards places where people want to leave and onto the places where they may try and end up. I can only hope, and dream myself, of a future where borders are gateways at which we welcome those who have made the journey. I imagine countries as places where living as legal, contributing, and recognized members of communities are made possible to all, socially and economically.

I think my personal experience is that akin of the Dreamers; children of immigrants whose past and futures are tied to the actions of their parents, the will of the people, and the policies enacted by governments. I do not perfectly fit this description but the journey, with its few commonalities, is etched into my being. The worry about how we support future Dreamers, asylum seekers, and immigrants as our world progresses into climate change and resource related conflict keeps me up at night.

The US has no idea how many illegal immigrants are truly in the country. I know this from personal experiences.. My experiences push to keep my needle pointing towards the positive, progressive, and welcoming end of the policy spectrum. Sometimes it feels like a lonely place to be, but I know that I’m not the only one.