Episode

Highlights

MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND

Julius Kolawole looks out over Bami Farm | Photo: Cheryl Adams

Since it was colonized by the English in the 1600s, Johnston has been a Yankee farming community. But that history makes it hard for newcomers like Julius Kolawole to feel welcome farming the same soil.

Garmin carrying water to her plot | Photo: Ana González

“Bami” in Swahili and Zulu means “mine”. Garmin is holding a pickaxe and standing in the middle of rows and rows of soil she just tilled by hand. It’s Memorial Day weekend, the first big push of the season here in Rhode Island. This year, Garmin hopes to produce even more vegetables to sell at the market than she did last season, so she doesn’t have much time to talk.

Up the hill on the plot farmed by refugees from Rwanda, The Congo, and Burundi | Photo: Cheryl Adams

AARI

Julius knows that many other African immigrants and refugees who come to Rhode Island have deep farming knowledge, but it can be difficult to transfer those skills to an American workforce and culture. In 2009, Julius starts a nonprofit called the African Alliance. Its goal is to connect newly-arrived African immigrants and refugees with support and a network of African people here, in Rhode Island.

Checking on the newly planted seedlings | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“Many of these people cannot write their names…But in terms of immigrants, we all experienced something similar. Being new. Not sure where you’re going. Not sure what’s gonna happen. Not sure who to call. All of those things is common to all of us.”

—JULIUS

Marie’s son, Christopher, holding his son, Samuel | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“When we began 2009, 2010, the mission was for these women to get out of the house, have a place to go. Because we are a village people. You know, I come to your door, you come to my door and so on and so forth. In America, you have an apartment, you have a key, you can’t go to the next door, no. Okay, so what we did was take them to a garden, so they can grow things to feed their family. And then they can go there and have an evening out of the apartment. We have pictures of things like that, where they’re sitting in the farm, just wiling away time. It’s like therapy for them.”

—JULIUS

Christopher planted these Rwandan bananas | Photo: Cheryl Adams

MAKING HISTORY

In 2013, Julius starts setting up African Alliance booths at farmers markets around Providence. Now, the women are earning money and connecting to the greater Rhode Island community. They’re selling typical American vegetables like potatoes, broccoli, and tomatoes, but they’re also selling things they grew up growing, like Okra, Uziza, Ewedu, different types of bananas.

The African Alliance at a pop-up market in 2019 | Photo courtesy African Alliance

“So exercise is good. Eating fresh vegetables is also good. On top of that you’re eating vegetables that you are familiar with. That’s even excellent! And this is the first time in the history of the state, to the best of my knowledge, that we grow African vegetables, sell African vegetables, make products from growth of African vegetable. To me, that’s historic.”

—JULIUS

Julius interviewed in June 2020 | Photo: Cheryl Adams

ASKING FOR HELP

Dame Family Farm and Orchard is one street over from Bami Farm. So, Julius goes there one day in the spring of 2019 to introduce himself and maybe get Darlene’s help setting up an irrigation system like hers.

“We went there. All we said to her is, ‘We are new here. And we just want to say hello to you. And if we ever need any help, we can come to you.’ ‘Oh, we don’t take anything from the government. No, no we been here since 1875.’”

—JULIUS

Dame Family Farm and Orchard sits on 40 acres of pristine, historic farmland | Photo: Ana González

What the Bami farmers don’t know is that Johnston, and the Dame Family Farm in particular, is at the center of a bitter land dispute that started over fifty years ago.

GREEN ACRES ACT

In 1964, the state of Rhode Island passes The Green Acres Act. This program promises to conserve forest and farm land for future generations of Rhode Islanders to use as such.

Archival footage compilation courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society

Green Acres takes 5,000 acres of land from Rhode Island landowners with the promise to build things like conservatories and parks. What it really does is place an economic value on conservation land that overrides the protection and land rights of Rhode Island citizens.

“You know, I loved haying. And the last year that we hayed, where Julius, because Julius farms the lower field way in the back. We all cried the entire time we were haying that June. It was the hardest thing we’d ever done. We knew we were leaving it. So that’s why some of some of the approaches that the politicians take and the people who are in charge, they don’t get it.”

—DARLENE DAME

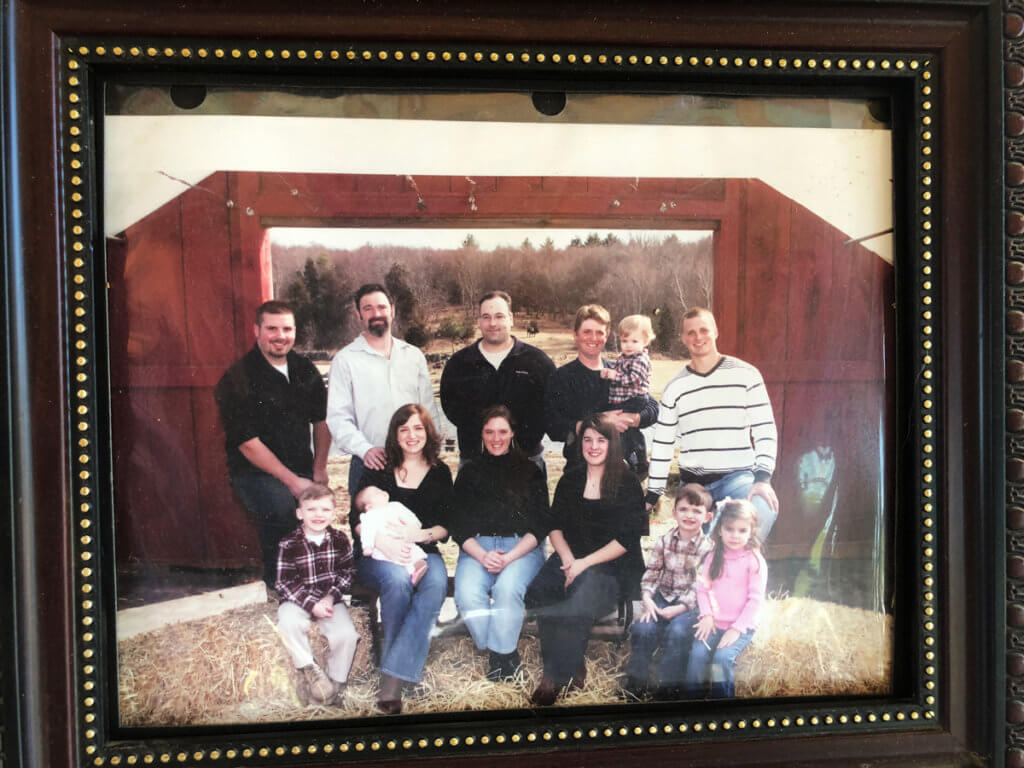

Darlene Dame’s children and grandchildren | Photo: Ana González

MAKE OURSELVES RICH

The Davis family visiting Bami Farm from Providence | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“I personally think that’s what we need to do to make ourselves rich. We did it to make America rich. Right? America has gotten rich off of Africans, Africans in America. And if we want to be wealthy, we need to go back to the land, make ourselves wealthy.”

—ARTHUR

Julius teaching Adonis how to care for seedlings | Photo: Cheryl Adams

“See this little boy? That’s my focus. And I’ll tell you why…People who look like me, don’t have that urge, don’t have that engineering demand… So if you catch them early, like this little one, maybe he may be interested in environmental issues. Maybe zoology, maybe botany. Why is the leaf green? What is called photosynthesis? You know, what, what is butterfly? You gotta catch them early. And I’m inviting them here because we all live in a three-level tenement. You don’t have the space. You don’t see trees. You see butterflies in your neighborhood you’re wondering, has something gone wrong? Hopefully, I’ve seen signs that this is gonna work.”

—JULIUS

Adonis and his cousin (Ana loves this photo) | Photo: Cheryl Adams