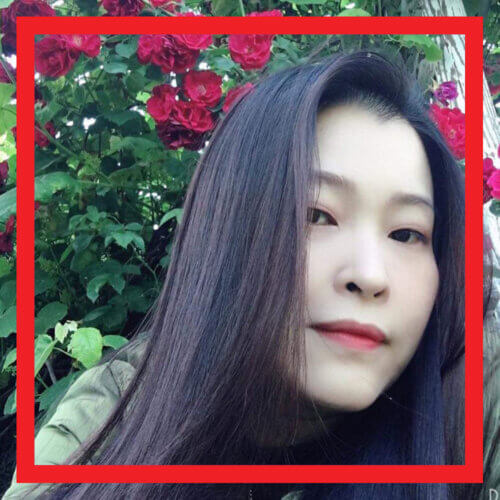

Mosaic Community Essays

"The Other"

I am an immigrant. My story of immigration is not a complicated nor a dramatic one.

It is an easy and simple one, yet it has shaped and impacted my life for over fifty years. I grew up in Paris from 1956 to 1970. My parents were Polish Jews who both survived the Holocaust. We lived in Le Marais; which was, then, a working-class Jewish neighborhood. My dad owned a small and always struggling garment manufacturing business. We referred to it as “l’atelier”. It was attached to our modest apartment. Most of my parents’ friends were Jews from eastern Europe; who all seem related to one another. Most of my friends were Jewish too.

I was quite assimilated and had a good and mostly joyful childhood and many of my fondest memories center around playing soccer with my friends. Although a mediocre player myself; I was passionate for the game and a big fan of the French national team. Growing up Jewish in the 1960’s also meant many stories of generational immigration, persecution, loss and trauma, and anti-Semitism. While born in Paris and being a French citizen, I was still somewhat of an outsider.

This was my early introduction to being “the other”.

My parents did a good job sparing my sister and I many details of their horrific past as well as their chronic financial difficulties and hardships. In 1969; France experienced a severe recession and my father’s business went bankrupt. He was too proud to ask for help from uncle Lova and aunt Rouska who operated a successful garment business. My dad’s solution, instead, was to return to New York City; where he had lived for several years after the war and before meeting my mother. With the help and sponsorship of a cousin, my dad found a well-paying union job in the garment district as a sample maker.

A few months later; on February 20th; 1970; my mom, older sister and I left Paris for our immigration journey. We arrived at JFK airport on a cold, colorless and dismal winter day. My dad proudly greeted us and a yellow cab took us to Brooklyn, where my father rented an apartment that was too small for the four of us. Every year since, I experience a bout of melancholia around Presidents Day weekend; our anniversary of leaving Paris and moving to the United States. To this day, I dislike flying into JFK international airport.

The move was traumatic. I left without saying goodbye to my many friends. It was a mixture of denial, sadness and shame. What was I going to say? “I will never see you again. We are moving to the USA because my father’s business went bankrupt and he selfishly ruined my life?”. I left my happy childhood; my friends and relatives and a city I knew by heart and loved. In many ways; my innocence and youth died.

The most difficult early issues were my loneliness and my inability to talk and express myself. In my Pre-move life I was articulate, outgoing, precocious and funny. In my Post-move life, I became self-conscious and timid. Five years of high school English in France equated to virtually no ability to string a coherent sentence together or have a reciprocal conversation. It was easier not to speak; not to have a voice.

No one I met saw or heard my exuberance, playfulness and social fluidity. I felt totally different; an observer, a bystander, a novelty. In a Brooklyn High School in 1970, I was the “other”. Ironically, I became more French after I immigrated to the US. Everyone reminded me, often in kind but annoying ways, that I was French. That was my identity.

Was I anything but French? I especially hated my accent; my inability to hide it, I wanted to blend in as much as I wanted to hide and disappear. The universal adolescent struggles for acceptance, belonging and identity were exponentially magnified for me.

I could not speak so I immersed myself in listening to rock music. The DJ’s on WNEW FM became my mentors, teachers and friends. I learned baseball by watching hundreds of games and studying the rules. I was drawn to ice hockey and all the French Canadians players. I missed soccer terribly and followed the French soccer team’s ascension to the top. I buried myself in comedies on TV such as “I Love Lucy” “Laugh in” and the “Carol Burnett show”. I had no social life.

I believe I learned fluent English binge-watching countless hours of television. I did not learn fluent English in a remedial speech class, I hated for accentuating my feelings of shame and otherness.

For most of high school I was angry and bitter at my parents and fantasized about my great and triumphant return to France at eighteen, but I eventually felt more confident in my ability to communicate. I started to come out of my shell, opened up, and began to reciprocate to friendly gestures, which I had previously and systematically rejected.

Being “the other” had changed me permanently. I had made some new friends and went out occasionally. I had reconnected with my best friend from childhood who spent a year living with a family in Connecticut and, once again, I did well in school. In spite of those positive developments I was now introverted, serious, and comfortable being alone. I still hated having an accent that gave it away. I dressed and looked like an American teenager but did not sound like one. I still felt different.

Unlike most American teenagers; I lived at home while attending Brooklyn College. There I quickly gravitated towards psychology and sociology. I was interested in understanding human behaviors, and emotions through the lens of an outsider. I especially wanted to understand normalcy and “deviancy” and became aware that there were many forms of otherness besides mine. It sets the early stage to my desire to help others.

While in college, I received my green card and later on became an American citizen. This process was easy. I was fortunate to be documented and privileged to be white, European and educated. Most significantly; I was able to keep my dual citizenship; which has been a source of comfort and security ever since.. Over time, I learnt that immigration and citizenship can be for many a daunting experience with difficult choices.

I went to graduate school in social work and became a psychotherapist. My career has now spanned over forty years. I believe that my professional identity and practice were molded by my experiences of immigration and othernerness as well as my conflicted needs to balance assimilating with holding on to my roots; in the context of adolescence’s identity struggles.

I believe that out of my struggles and pains of my immigrant experience, I developed openness, respect, tolerance, curiosity; empathy and compassion for others, especially those who do not fit in, feel disenfranchised; ostracized, devalued or without a voice. I also believe that being bicultural made me seehuman beings and human behaviors as a non-binary spectrum. I developed the tendency to cheer for and support the underprivileged, to view life from multiple angles and perspectives, and to value the relative over the absolute.

Those perspectives have been especially helpful in treating adolescents, couples and families as well as many international students. On occasions I have treated French speaking patients. It is rewarding but also challenging; as my “therapist’s voice” is usually one of an adult English- speaking male.

In stories of immigration as well as stories of childhood pain and suffering; I often see courage, resiliency, adaptability and the complexity of the human condition. We all have many parts and many identities. I would not be a passionate therapist; nor have as strong of a moral compass if not from the pains of adolescence and immigration. While people’s histories, backgrounds and cultures are different, people are fundamentally similar in what they need for themselves, their loved ones, and their communities.

Last February I celebrated my fiftieth anniversary of moving to the United States. I am now more at ease with embracing my two cultures and being both a foreigner and a citizen. I still root for the French men’s soccer team and celebrated their World Cup victories in 1998 and 2018. I also now root for the American Women’s soccer team.

Paradoxically; the more comfortable I become with my American part; the more I cherish my French part too. I love that my children (both dual citizens); whom attended the French American school of Rhode Island for five years have a strong sense of their bicultural identities.

This has been especially true since they returned home from their respective college study abroad programs in Paris. Visiting them and living the French experience through their eyes had a huge impact on my own integration process. While in France, I often feel contrary feelings. I am back home; in my heart; yet I often see through the naïve and romantic eye of a wandering American tourist. I feel whole with both my French and American sides now. Before, being different was a source of shame, alienation and embarrassment. Now I can celebrate my differences as a source of pride; richness and gratitude. I can love my French and American parts and love France and the USA in spite of their flaws and imperfections.I can join; I can belong but I can also stay on the periphery.

In those current polarizing times, the” other” has been irrationally vilified through extreme mistrust and judgement. It is driven by fear, intolerance, stereotypes and lack of knowledge.

The” other” is the one that does not look, speak, vote or act like us. The other comes from somewhere else, the place of imaginary threats and dangers. We have, however, opportunities to greet and treat all immigrants and all “others” with curiosity, humility, respect and compassion. In doing so; we open the door for mutually enriching connections and contributions. I am grateful that as an immigrant,a privileged one granted, I use my history and experience to recognize and try to remove the demarcation between us and them.